↧

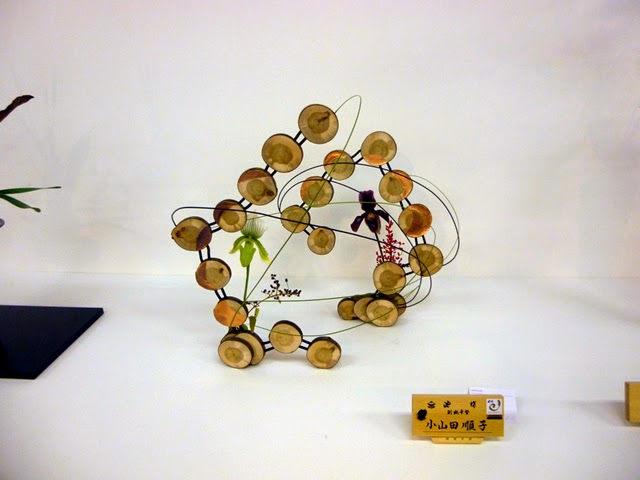

Ikenobo ex h26 hanashoyo Tanabatakai

↧

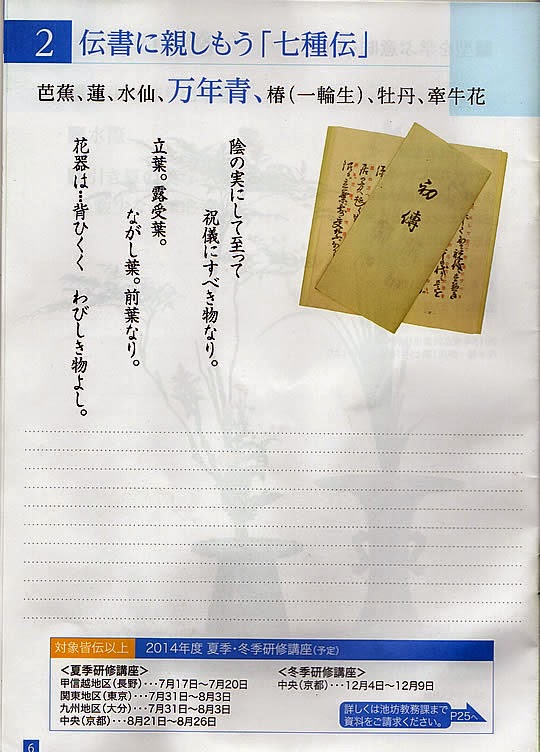

Ikenobo ex h26 hanashoyo Tanabatakai p2

↧

↧

kado lesson mayumi

↧

Did Korea encourage sex work at US bases?

http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-27189951

9 June 2014 Last updated at 23:06

Did Korea encourage sex work at US bases?

The rubbish collector left on the scrap heap as his city goes green

How I drank urine and bat blood to survive

Left to the mercy of the Taliban

Koreans could once be sure that their children would look after them in their old age, but no longer - many of those who worked hard to transform the country's economy find the next generation has other spending priorities. As a result, some elderly women are turning to prostitution.

Kim Eun-ja sits on the steps at Seoul's Jongno-3 subway station, scanning the scene in front of her. The 71-year-old's bright lipstick and shiny red coat stand out against her papery skin.

Beside her is a large bag, from which comes the clink of glass bottles as she shifts on the cold concrete.

Mrs Kim is one of South Korea's "Bacchus Ladies" - older women who make a living by selling tiny bottles of the popular Bacchus energy drink to male customers.

But often that's not all they're selling. At an age when Korean grandmothers are supposed to be venerated as matriarchs, some are selling sex.

Continue reading the main story

“

Start Quote

I can't trust my children to help - they're in deep trouble because they have to start preparing for their old age”

Mr Kim

"You see those Bacchus Ladies standing over there?" she asks me. "Those ladies sell more than Bacchus. They sometimes go out with the grandpas and earn money from them. But I don't make a living like that.

"Men do proposition me when I'm standing in the alleyway," she adds. "But I always say, 'No.'"

Mrs Kim says she makes about 5,000 Won ($5, or £3) a day selling the drinks. "Drink up fast," she says. "The police are always watching me. They don't differentiate."

The centre of this underground sex trade is a nearby park in the heart of Seoul. Jongmyo Park is a place where elderly men come to while away their sunset years with a little chess and some local gossip.

Men playing board game in Jongmyo park

It's built around a temple to Confucius, whose ideas on venerating elders have shaped Korean culture for centuries. But under the budding trees outside, the fumbling transactions of its elderly men and women tell the real story of Korean society in the 21st Century.

Women in their 50s, 60, even their 70s, stand around the edges of the park, offering drinks to the men. Buy one, and it's the first step in a lonely journey that ends in a cheap motel nearby.

The men in the park are more willing to talk to me than the women.

Continue reading the main story

Find out more

Stock image of Korean woman (posed by model)

Listen to Lucy Williamson's report for Assignment on the BBC World Service on Thursday - or catch up later on the BBC iPlayer

Standing around a game of Korean chess, a group of grandfathers watch the match intently. About half the men here use the Bacchus Ladies, they say.

"We're men, so we're curious about women," says 60-year-old Mr Kim.

"We have a drink, and slip a bit of money into their hands, and things happen!" he cackles. "Men like to have women around - whether they're old or not, sexually active or not. That's just male psychology."

Another man, 81 years old, excitedly showed me his spending money for the day. "It's for drinking with my friends," he said. "We can find girlfriends here, too - from those women standing over there. They'll ask us to play with them. They say, 'Oh, I don't have any money,' and then they glue on to us. Sex with them costs 20,000 to 30,000 Won (£11-17), but sometimes they'll give you a discount if they know you."

South Korea's grandparents are victims of their country's economic success.

As they worked to create Korea's economic miracle, they invested their savings in the next generation. In a Confucian society, successful children are the best form of pension.

But attitudes here have changed just as fast as living standards, and now many young people say they can't afford to support themselves and their parents in Korea's fast-paced, highly competitive society.

Woman and ad for Korean smartphone

The government, caught out by this rapid change, is scrambling to provide a welfare system that works. In the meantime, the men and women in Jongmyo Park have no savings, no realistic pension, and no family to rely on. They've become invisible - foreigners in their own land.

Continue reading the main story

“

Start Quote

One Bacchus woman said to me 'I'm hungry, I don't need respect, I don't need honour, I just want three meals a day'”

Dr Lee Ho-Sun

"Those who rely on their children are stupid," says Mr Kim. "Our generation was submissive to our parents. We respected them. The current generation is more educated and experienced, so they don't listen to us.

"I'm 60 years old and I don't have any money. I can't trust my children to help. They're in deep trouble because they have to start preparing for their old age. Almost all of the old folks here are in the same situation."

Most Bacchus women have only started selling sex later in life, as a result of this new kind of old-age poverty, according to Dr Lee Ho-Sun, who is perhaps the only researcher to have studied them in detail.

One woman she interviewed first turned to prostitution at the age of 68. About 400 women work in the park, she says, all of whom will have been taught as children that respect and honour were worth more than anything.

"One Bacchus woman said to me 'I'm hungry, I don't need respect, I don't need honour, I just want three meals a day," Lee says.

Police, who routinely patrol the area but are rarely able to make an arrest, privately say this problem will never be solved by crackdowns, that senior citizens need an outlet for stress and sexual desire, and that policy needs to change.

But law-enforcement isn't the only problem.

Graffiti on the street showing an elderly couple kissing

Graffiti on a street on Seoul

Inside those bags the Bacchus Ladies carry is the source of a hidden epidemic: a special injection supposed to help older men achieve erections - delivered directly into the vein. Dr Lee confirms that the needles aren't disposed of afterwards, but used again - 10 or 20 times.

The results, she says, can be seen in one local survey, which found that almost 40% of the men tested had a sexually transmitted disease¬ despite the fact that some of the most common diseases weren't included in the test. With most sex education classes aimed at teenagers, this has the makings of a real problem. Some local governments have now begun offering sex education clinics especially for seniors.

Hidden in a dingy warren of alleyways in central Seoul, is the place where these lonely journeys end - the narrow corridors of a "love motel" and one of the grey rooms which open off them.

Inside, a large bed takes up most of the space, its thin mattress and single pillow hardly inviting a long night's sleep. On the bed-head is a sticker: for room service press zero; for pornography press three; and if you want the electric blanket, you'll find the wire on the far side of the bed.

So here you have food, sex, and even a little warmth all at the touch of a button. If only it were that simple outside the motel room, in South Korea's rich, hi-tech society.

But for the grandparents who built its fearsome economy, food is expensive, sex is cheap, and human warmth rarely available at any price.

http://www.koreabang.com/2013/stories/north-korean-defector-working-as-prostitute-found-dead-in-motel.html

North Korean Defector Working as Prostitute Found Dead in Motel

by Harald Olsen on Thursday, March 28, 2013 72 comments

defector prostituteTwo defectors leave a car, from a 2012 photo essay by Kim Jong Taek

Earlier this month, the body of a defector and known prostitute was found in a motel room in the city of Hwaseong, sparking debate regarding the treatment of North Koreans who come to the South.

The murderer turned himself in to the police within 24 hours of the crime he said he had committed ‘in a fit of anger’ when the woman refused to participate in a ‘perverted’ sex act.

The story of the woman’s difficult journey to South Korea, leaving the North in 2002 with her siblings and passing through Cambodia before finally arriving in the South won the sympathy of many netizens who hoped she could be ‘reborn’ into a better life. The fact that the murderer already had 16 convictions incited outrage and renewed calls for greater use of the death penalty.

Prostitution can be a common path for female defectors, experts cited in articles covering the incident said. The women, who often need to repay smugglers who extract them from the North and guide them through China, can become easily recruited by other defectors who have themselves turned to prostitution.

From Yonhap News:

Tragedy as defector forced into prostitution is murdered

The tragic story of a female defector strangled by one of her clients has recently emerged. The woman, who worked in a tea house, was delivering tea to a client when she was strangled.

The manager of a motel in the city of Hwaseong in Gyeonggi Province, found Ms. Kim, age forty-five, in one of his rooms at 11:20 p.m. on the night of March 17th.

The assailant has been identified as a Mr. Lee, who checked into a room at the motel at 2:00 p.m.

According to the police, Lee was driven to strangle Ms. Kim after she rejected his request for a perverted sex act after he had paid her and they were engaged in sexual relations. Angered by the rejection, Lee suddenly attacked the woman and strangled her.

Lee turned himself in on the 18th and admitted his crime. The police immediately arrested him for the charge of murder.

Kim had left North Korea with three of her siblings in 2002.

After spending two years in China, Kim sought asylum in Cambodia in May of 2004. Embracing dreams of ‘new life in South Korea’, she arrived in Incheon Airport in June of the same year and began a new life.

While Kim never formally married, she set up a home in the city of Suwon. However, her ‘second life’ was not to last for very long. After nine years in South Korea, her life ended in tragedy.

The police report contained comments from an employee at the tea house, ‘Ms. Kim had been working here for the past two days, she also came here to work about twenty days ago…When she first came looking for work she mentioned that she had worked at a hair salon in the past.’

defector prostitute2

Female defectors making the journey to South Korea through another intermediary country often experience severe mental and physical harm, which may not end even after they have started a new life.

In a 2012 Yonsei University School of Welfare study commissioned by the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 26.4% of surveyed female defectors between the ages of twenty and fifty showed signs of psychological depression, (37 of the 140 respondents).

14.3% of the survey respondents said that they had been the victim of sexual assault, molestation, or sexual violence while they were living in North Korea. The percentage of respondents who said they had suffered injury while traveling through a third country was even higher at 17.9%. 12.1% of respondents said they had suffered after arriving in South Korea.

According to Kim Jae-yeob, Dean of the Yonsei University Graduate School of Welfare, ‘Female defectors endure violence not only while they are in North Korea or while traveling through a third county, but also after they move to South Korea. This violence becomes a very serious threat to their independence. He emphasised the need for a plan that would provide customised support to female defectors who have suffered violence.

http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/bulletin/2013/03/18/0200000000AKR20130318189200061.HTML?input=1179m

<성매매 내몰렸다 살해된 탈북 여성의 비극>

(화성=연합뉴스) 이우성 기자 = 여관으로 차 배달을 갔다가 투숙객에게 목 졸려 살해된 탈북자 출신 다방 여종업원의 사연이 주위를 안타깝게 하고 있다.

경기도 화성의 한 다방에서 여종업원으로 일하던 탈북 여성 김모(45)씨는 17일 오후 11시 20분께 다방 인근 한 여관 객실에서 목 졸려 숨진 채 여관 지배인에 의해 발견됐다.

범인은 오후 2시께 여관에 투숙한 이모(34·무직)씨.

이씨가 경찰에서 밝힌 살해동기는 돈을 주고 성매매를 제안해 성관계를 갖다가 변태적 성행위를 요구했는데, 김씨가 욕을 하며 거부해 홧김에 목을 졸라 살해했다는 것이다.

경찰은 18일 오전 자수해 범행 사실을 털어놓은 이씨를 긴급체포한 뒤 살인 등 혐의로 구속영장을 신청했다.

숨진 김씨는 2002년 언니 등 형제 3명과 함께 탈북했다.

중국에서 2년여 동안 머물다가 2004년 5월 캄보디아로 망명한 뒤 '남한 사회'에 대한 꿈을 안고 같은 해 6월 인천공항을 통해 남한에 들어와 정착했다.

2∼3년 전 탈북자 출신인 남자를 만나 가정도 꾸렸다.

혼인 신고는 하지 않았지만 수원에 보금자리를 마련해 '제2의 인생'을 꿈꾸던 김씨의 삶은 오래가지 않았다. 남한 생활은 9년 만에 비극으로 막을 내렸다.

다방 관계자는 경찰 조사에서 "김씨는 16일부터 이틀간 나와 일했고, 20여일 전에도 이틀만 일했었다"며 "일자리를 구하려고 처음 찾아왔을 때 미용 일을 했었다고 했다"며 안타까워했다.

탈북 여성들은 북한에서 제3국을 거쳐 남한 사회에 정착하는 과정에서 심각한 정신적, 신체적 피해를 경험하고 있다.

여성가족부가 연세대 사회복지대학원에 의뢰해 지난해 3∼8월 20∼50대 탈북 여성 140명을 대상으로 조사한 결과에 따르면 전체의 26.4%(37명)가 주요 우울 장애로 의심되는 심리상태를 보였다.

응답자의 14.3%(20명)는 북한 체류 당시에 성폭행이나 성추행 등 성폭력에 시달린 것으로 조사됐다. 제3국을 통한 탈북 과정이나 남한 정착 후 피해를 봤다는 응답자도 각각 17.9%(25명), 12.1%(17명)에 달했다.

당시 조사결과를 내놓은 김재엽 연세대 사회복지대학원장은 "북한과 제3국 경유 과정뿐만 아니라 남한에 이주한 이후에도 계속 경험하는 폭력 피해는 탈북여성의 자립에 심각한 장애요인이 되고 있다"며 폭력피해 탈북여성에 대한 맞춤형 자립지원 방안의 필요성을 강조한 바 있다.

gaonnuri@yna.co.kr

<저작권자(c)연합뉴스. 무단전재-재배포금지.>2013/03/18 19:43 송고

9 June 2014 Last updated at 23:06

Did Korea encourage sex work at US bases?

The rubbish collector left on the scrap heap as his city goes green

How I drank urine and bat blood to survive

Left to the mercy of the Taliban

Koreans could once be sure that their children would look after them in their old age, but no longer - many of those who worked hard to transform the country's economy find the next generation has other spending priorities. As a result, some elderly women are turning to prostitution.

Kim Eun-ja sits on the steps at Seoul's Jongno-3 subway station, scanning the scene in front of her. The 71-year-old's bright lipstick and shiny red coat stand out against her papery skin.

Beside her is a large bag, from which comes the clink of glass bottles as she shifts on the cold concrete.

Mrs Kim is one of South Korea's "Bacchus Ladies" - older women who make a living by selling tiny bottles of the popular Bacchus energy drink to male customers.

But often that's not all they're selling. At an age when Korean grandmothers are supposed to be venerated as matriarchs, some are selling sex.

Continue reading the main story

“

Start Quote

I can't trust my children to help - they're in deep trouble because they have to start preparing for their old age”

Mr Kim

"You see those Bacchus Ladies standing over there?" she asks me. "Those ladies sell more than Bacchus. They sometimes go out with the grandpas and earn money from them. But I don't make a living like that.

"Men do proposition me when I'm standing in the alleyway," she adds. "But I always say, 'No.'"

Mrs Kim says she makes about 5,000 Won ($5, or £3) a day selling the drinks. "Drink up fast," she says. "The police are always watching me. They don't differentiate."

The centre of this underground sex trade is a nearby park in the heart of Seoul. Jongmyo Park is a place where elderly men come to while away their sunset years with a little chess and some local gossip.

Men playing board game in Jongmyo park

It's built around a temple to Confucius, whose ideas on venerating elders have shaped Korean culture for centuries. But under the budding trees outside, the fumbling transactions of its elderly men and women tell the real story of Korean society in the 21st Century.

Women in their 50s, 60, even their 70s, stand around the edges of the park, offering drinks to the men. Buy one, and it's the first step in a lonely journey that ends in a cheap motel nearby.

The men in the park are more willing to talk to me than the women.

Continue reading the main story

Find out more

Stock image of Korean woman (posed by model)

Listen to Lucy Williamson's report for Assignment on the BBC World Service on Thursday - or catch up later on the BBC iPlayer

Standing around a game of Korean chess, a group of grandfathers watch the match intently. About half the men here use the Bacchus Ladies, they say.

"We're men, so we're curious about women," says 60-year-old Mr Kim.

"We have a drink, and slip a bit of money into their hands, and things happen!" he cackles. "Men like to have women around - whether they're old or not, sexually active or not. That's just male psychology."

Another man, 81 years old, excitedly showed me his spending money for the day. "It's for drinking with my friends," he said. "We can find girlfriends here, too - from those women standing over there. They'll ask us to play with them. They say, 'Oh, I don't have any money,' and then they glue on to us. Sex with them costs 20,000 to 30,000 Won (£11-17), but sometimes they'll give you a discount if they know you."

South Korea's grandparents are victims of their country's economic success.

As they worked to create Korea's economic miracle, they invested their savings in the next generation. In a Confucian society, successful children are the best form of pension.

But attitudes here have changed just as fast as living standards, and now many young people say they can't afford to support themselves and their parents in Korea's fast-paced, highly competitive society.

Woman and ad for Korean smartphone

The government, caught out by this rapid change, is scrambling to provide a welfare system that works. In the meantime, the men and women in Jongmyo Park have no savings, no realistic pension, and no family to rely on. They've become invisible - foreigners in their own land.

Continue reading the main story

“

Start Quote

One Bacchus woman said to me 'I'm hungry, I don't need respect, I don't need honour, I just want three meals a day'”

Dr Lee Ho-Sun

"Those who rely on their children are stupid," says Mr Kim. "Our generation was submissive to our parents. We respected them. The current generation is more educated and experienced, so they don't listen to us.

"I'm 60 years old and I don't have any money. I can't trust my children to help. They're in deep trouble because they have to start preparing for their old age. Almost all of the old folks here are in the same situation."

Most Bacchus women have only started selling sex later in life, as a result of this new kind of old-age poverty, according to Dr Lee Ho-Sun, who is perhaps the only researcher to have studied them in detail.

One woman she interviewed first turned to prostitution at the age of 68. About 400 women work in the park, she says, all of whom will have been taught as children that respect and honour were worth more than anything.

"One Bacchus woman said to me 'I'm hungry, I don't need respect, I don't need honour, I just want three meals a day," Lee says.

Police, who routinely patrol the area but are rarely able to make an arrest, privately say this problem will never be solved by crackdowns, that senior citizens need an outlet for stress and sexual desire, and that policy needs to change.

But law-enforcement isn't the only problem.

Graffiti on the street showing an elderly couple kissing

Graffiti on a street on Seoul

Inside those bags the Bacchus Ladies carry is the source of a hidden epidemic: a special injection supposed to help older men achieve erections - delivered directly into the vein. Dr Lee confirms that the needles aren't disposed of afterwards, but used again - 10 or 20 times.

The results, she says, can be seen in one local survey, which found that almost 40% of the men tested had a sexually transmitted disease¬ despite the fact that some of the most common diseases weren't included in the test. With most sex education classes aimed at teenagers, this has the makings of a real problem. Some local governments have now begun offering sex education clinics especially for seniors.

Hidden in a dingy warren of alleyways in central Seoul, is the place where these lonely journeys end - the narrow corridors of a "love motel" and one of the grey rooms which open off them.

Inside, a large bed takes up most of the space, its thin mattress and single pillow hardly inviting a long night's sleep. On the bed-head is a sticker: for room service press zero; for pornography press three; and if you want the electric blanket, you'll find the wire on the far side of the bed.

So here you have food, sex, and even a little warmth all at the touch of a button. If only it were that simple outside the motel room, in South Korea's rich, hi-tech society.

But for the grandparents who built its fearsome economy, food is expensive, sex is cheap, and human warmth rarely available at any price.

http://www.koreabang.com/2013/stories/north-korean-defector-working-as-prostitute-found-dead-in-motel.html

North Korean Defector Working as Prostitute Found Dead in Motel

by Harald Olsen on Thursday, March 28, 2013 72 comments

defector prostituteTwo defectors leave a car, from a 2012 photo essay by Kim Jong Taek

Earlier this month, the body of a defector and known prostitute was found in a motel room in the city of Hwaseong, sparking debate regarding the treatment of North Koreans who come to the South.

The murderer turned himself in to the police within 24 hours of the crime he said he had committed ‘in a fit of anger’ when the woman refused to participate in a ‘perverted’ sex act.

The story of the woman’s difficult journey to South Korea, leaving the North in 2002 with her siblings and passing through Cambodia before finally arriving in the South won the sympathy of many netizens who hoped she could be ‘reborn’ into a better life. The fact that the murderer already had 16 convictions incited outrage and renewed calls for greater use of the death penalty.

Prostitution can be a common path for female defectors, experts cited in articles covering the incident said. The women, who often need to repay smugglers who extract them from the North and guide them through China, can become easily recruited by other defectors who have themselves turned to prostitution.

From Yonhap News:

Tragedy as defector forced into prostitution is murdered

The tragic story of a female defector strangled by one of her clients has recently emerged. The woman, who worked in a tea house, was delivering tea to a client when she was strangled.

The manager of a motel in the city of Hwaseong in Gyeonggi Province, found Ms. Kim, age forty-five, in one of his rooms at 11:20 p.m. on the night of March 17th.

The assailant has been identified as a Mr. Lee, who checked into a room at the motel at 2:00 p.m.

According to the police, Lee was driven to strangle Ms. Kim after she rejected his request for a perverted sex act after he had paid her and they were engaged in sexual relations. Angered by the rejection, Lee suddenly attacked the woman and strangled her.

Lee turned himself in on the 18th and admitted his crime. The police immediately arrested him for the charge of murder.

Kim had left North Korea with three of her siblings in 2002.

After spending two years in China, Kim sought asylum in Cambodia in May of 2004. Embracing dreams of ‘new life in South Korea’, she arrived in Incheon Airport in June of the same year and began a new life.

While Kim never formally married, she set up a home in the city of Suwon. However, her ‘second life’ was not to last for very long. After nine years in South Korea, her life ended in tragedy.

The police report contained comments from an employee at the tea house, ‘Ms. Kim had been working here for the past two days, she also came here to work about twenty days ago…When she first came looking for work she mentioned that she had worked at a hair salon in the past.’

defector prostitute2

Female defectors making the journey to South Korea through another intermediary country often experience severe mental and physical harm, which may not end even after they have started a new life.

In a 2012 Yonsei University School of Welfare study commissioned by the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, 26.4% of surveyed female defectors between the ages of twenty and fifty showed signs of psychological depression, (37 of the 140 respondents).

14.3% of the survey respondents said that they had been the victim of sexual assault, molestation, or sexual violence while they were living in North Korea. The percentage of respondents who said they had suffered injury while traveling through a third country was even higher at 17.9%. 12.1% of respondents said they had suffered after arriving in South Korea.

According to Kim Jae-yeob, Dean of the Yonsei University Graduate School of Welfare, ‘Female defectors endure violence not only while they are in North Korea or while traveling through a third county, but also after they move to South Korea. This violence becomes a very serious threat to their independence. He emphasised the need for a plan that would provide customised support to female defectors who have suffered violence.

http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/bulletin/2013/03/18/0200000000AKR20130318189200061.HTML?input=1179m

<성매매 내몰렸다 살해된 탈북 여성의 비극>

(화성=연합뉴스) 이우성 기자 = 여관으로 차 배달을 갔다가 투숙객에게 목 졸려 살해된 탈북자 출신 다방 여종업원의 사연이 주위를 안타깝게 하고 있다.

경기도 화성의 한 다방에서 여종업원으로 일하던 탈북 여성 김모(45)씨는 17일 오후 11시 20분께 다방 인근 한 여관 객실에서 목 졸려 숨진 채 여관 지배인에 의해 발견됐다.

범인은 오후 2시께 여관에 투숙한 이모(34·무직)씨.

이씨가 경찰에서 밝힌 살해동기는 돈을 주고 성매매를 제안해 성관계를 갖다가 변태적 성행위를 요구했는데, 김씨가 욕을 하며 거부해 홧김에 목을 졸라 살해했다는 것이다.

경찰은 18일 오전 자수해 범행 사실을 털어놓은 이씨를 긴급체포한 뒤 살인 등 혐의로 구속영장을 신청했다.

숨진 김씨는 2002년 언니 등 형제 3명과 함께 탈북했다.

중국에서 2년여 동안 머물다가 2004년 5월 캄보디아로 망명한 뒤 '남한 사회'에 대한 꿈을 안고 같은 해 6월 인천공항을 통해 남한에 들어와 정착했다.

2∼3년 전 탈북자 출신인 남자를 만나 가정도 꾸렸다.

혼인 신고는 하지 않았지만 수원에 보금자리를 마련해 '제2의 인생'을 꿈꾸던 김씨의 삶은 오래가지 않았다. 남한 생활은 9년 만에 비극으로 막을 내렸다.

다방 관계자는 경찰 조사에서 "김씨는 16일부터 이틀간 나와 일했고, 20여일 전에도 이틀만 일했었다"며 "일자리를 구하려고 처음 찾아왔을 때 미용 일을 했었다고 했다"며 안타까워했다.

탈북 여성들은 북한에서 제3국을 거쳐 남한 사회에 정착하는 과정에서 심각한 정신적, 신체적 피해를 경험하고 있다.

여성가족부가 연세대 사회복지대학원에 의뢰해 지난해 3∼8월 20∼50대 탈북 여성 140명을 대상으로 조사한 결과에 따르면 전체의 26.4%(37명)가 주요 우울 장애로 의심되는 심리상태를 보였다.

응답자의 14.3%(20명)는 북한 체류 당시에 성폭행이나 성추행 등 성폭력에 시달린 것으로 조사됐다. 제3국을 통한 탈북 과정이나 남한 정착 후 피해를 봤다는 응답자도 각각 17.9%(25명), 12.1%(17명)에 달했다.

당시 조사결과를 내놓은 김재엽 연세대 사회복지대학원장은 "북한과 제3국 경유 과정뿐만 아니라 남한에 이주한 이후에도 계속 경험하는 폭력 피해는 탈북여성의 자립에 심각한 장애요인이 되고 있다"며 폭력피해 탈북여성에 대한 맞춤형 자립지원 방안의 필요성을 강조한 바 있다.

gaonnuri@yna.co.kr

<저작권자(c)연합뉴스. 무단전재-재배포금지.>2013/03/18 19:43 송고

↧

kado lesson

↧

↧

Rewriting the War, Japanese Right Attacks a Newspaper

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/03/world/asia/japanese-right-attacks-newspaper-on-the-left-emboldening-war-revisionists.html?_r=0

Rewriting the War, Japanese Right Attacks a Newspaper

By MARTIN FACKLERDEC. 2, 2014

Photo

Takashi Uemura, a former journalist, is under attack for his reporting on “comfort women.” Credit Ko Sasaki for The New York Times

Continue reading the main storyContinue reading the main storyShare This Page

Continue reading the main story

SAPPORO, Japan — Takashi Uemura was 33 when he wrote the article that would make his career. Then an investigative reporter for The Asahi Shimbun, Japan’s second-largest newspaper, he examined whether the Imperial Army had forced women to work in military brothels during World War II. His report, under the headline “Remembering Still Brings Tears,” was one of the first to tell the story of a former “comfort woman” from Korea.

Fast-forward a quarter century, and that article has made Mr. Uemura, now 56 and retired from journalism, a target of Japan’s political right. Tabloids brand him a traitor for disseminating “Korean lies” that they say were part of a smear campaign aimed at settling old scores with Japan. Threats of violence, Mr. Uemura says, have cost him one university teaching job and could soon rob him of a second. Ultranationalists have even gone after his children, posting Internet messages urging people to drive his teenage daughter to suicide.

The threats are part of a broad, vitriolic assault by the right-wing news media and politicians here on The Asahi, which has long been the newspaper that Japanese conservatives love to hate. The battle is also the most recent salvo in a long-raging dispute over Japan’s culpability for its wartime behavior that has flared under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s right-leaning government.

This latest campaign, however, has gone beyond anything postwar Japan has seen before, with nationalist politicians, including Mr. Abe himself, unleashing a torrent of abuse that has cowed one of the last strongholds of progressive political influence in Japan. It has also emboldened revisionists calling for a reconsideration of the government’s 1993 apology for the wartime coercion of women into prostitution.

“They are using intimidation as a way to deny history,” said Mr. Uemura, who spoke with a pleading urgency and came to an interview in this northern city with stacks of papers to defend himself. “They want to bully us into silence.”

“The War on The Asahi,” as commentators have called it, began in August when the newspaper bowed to public criticism and retracted at least a dozen articles published in the 1980s and early ’90s. Those articles cited a former soldier, Seiji Yoshida, who claimed to have helped abduct Korean women for the military brothels. Mr. Yoshida was discredited two decades ago, but the Japanese right pounced on The Asahi’s gesture and called for a boycott to drive the 135-year-old newspaper out of business.

Speaking to a parliamentary committee in October, Mr. Abe said The Asahi’s “mistaken reporting had caused many people injury, sorrow, pain and anger. It wounded Japan’s image.”

With elections this month, analysts say conservatives are trying to hobble the nation’s leading left-of-center newspaper. The Asahi has long supported greater atonement for Japan’s wartime militarism and has opposed Mr. Abe on other issues. But it is increasingly isolated as the nation’s liberal opposition remains in disarray after a crushing defeat at the polls two years ago.

Continue reading the main story

Mr. Abe and his political allies have also seized on The Asahi’s woes as a long-awaited chance to go after bigger game: the now internationally accepted view that the Japanese military coerced tens of thousands of Korean and other foreign women into sexual slavery during the war.

Most mainstream historians agree that the Imperial Army treated women in conquered territories as spoils of battle, rounding them up to work in a system of military-run brothels known as comfort stations that stretched from China to the South Pacific. Many were deceived with offers of jobs in factories and hospitals and then forced to provide sex for imperial soldiers in the comfort stations. In Southeast Asia, there is evidence that Japanese soldiers simply kidnapped women to work in the brothels.

Among the women who have come forward to say they were forced to have sex with soldiers are Chinese, Koreans and Filipinos, as well as Dutch women captured in Indonesia, then a Dutch colony.

There is little evidence that the Japanese military abducted or was directly involved in entrapping women in Korea, which had been a Japanese colony for decades when the war began, although the women and activists who support them say the women were often deceived and forced to work against their will.

The revisionists, however, have seized on the lack of evidence of abductions to deny that any women were held captive in sexual slavery and to argue that the comfort women were simply camp-following prostitutes out to make good money.

For scholars of the comfort women issue, the surprise was not The Asahi’s conclusion that Mr. Yoshida had lied — the newspaper acknowledged in 1997 that it could not verify his account — but that it waited so long to issue a formal retraction. Employees at The Asahi said it finally acted because members of the Abe government had been using the articles to criticize its reporters, and it hoped to blunt the attacks by setting the record straight.

Instead, the move prompted a storm of denunciations and gave the revisionists a new opening to promote their version of history. They are also pressing a claim that has left foreign experts scratching their heads in disbelief: that The Asahi alone is to blame for persuading the world that the comfort women were victims of coercion.

Though dozens of women have come forward with testimony about their ordeals, the Japanese right contends it was The Asahi’s reporting that resulted in international condemnation of Japan, including a 2007 resolution by the United States House of Representatives calling on Japan to apologize for “one of the largest cases of human trafficking in the 20th century.”

Continue reading the main story

RECENT COMMENTS

Alan Attlee 2 hours ago

In 1937 the Japanese Army raped and murdered several hundred thousand people in NanJing. It was convenient to MacArthur to allow...

Justice 2 hours ago

This is the fact you cannot change that he spread the hoax, not the fact, and it's obvious that he has to pay it then.Also New York Times...

hedwig 2 hours ago

Please read the following article written by Mr. Michael Yon, a highly respected US author.//// quote ////There are growing, unsubstantiated...

SEE ALL COMMENTS WRITE A COMMENT

For conservatives, humbling The Asahi is also a way to advance their long-held agenda of erasing portrayals of Imperial Japan that they consider too negative and eventually overturning the 1993 apology to comfort women, analysts say. Many on the right have argued that Japan’s behavior was no worse than that of other World War II combatants, including the United States’ bombing of Japanese civilians.

Continue reading the main storyContinue reading the main storyContinue reading the main story

“The Asahi’s admission is a chance for the revisionist right to say: ‘See! We told you so!’ ” said Koichi Nakano, a political scientist at Sophia University in Tokyo. “Abe sees this as his chance to go after a historical issue that he believes has hurt Japan’s national honor.”

The Asahi’s conservative competitor, The Yomiuri Shimbun, the world’s highest-circulation newspaper, has capitalized on its rival’s troubles by distributing leaflets that highlight The Asahi’s mistakes in reporting on comfort women. Since August, The Asahi’s daily circulation has dropped by 230,797 to about seven million, according to the Japan Audit Bureau of Circulations.

Right-wing tabloids have gone further, singling out Mr. Uemura as a “fabricator of the comfort women” even though his article was not among those that The Asahi retracted.

Mr. Uemura said The Asahi had been too fearful to defend him, or even itself. In September, the newspaper’s top executives apologized on television and fired the chief editor.

CONTINUE READING THE MAIN STORY

198

COMMENTS

“Abe is using The Asahi’s problems to intimidate other media into self-censorship,” said Jiro Yamaguchi, a political scientist who helped organize a petition to support Mr. Uemura. “This is a new form of McCarthyism.”

Hokusei Gakuen University, a small Christian college where Mr. Uemura lectures on local culture and history, said it was reviewing his contract because of bomb threats by ultranationalists. On a recent afternoon, some of Mr. Uemura’s supporters gathered to hear a sermon warning against repeating the mistakes of the dark years before the war, when the nation trampled dissent.

Mr. Uemura did not attend, explaining that he was now reluctant to appear in public. “This is the right’s way of threatening other journalists into silence,” he said. “They don’t want to suffer the same fate that I have.”

A version of this article appears in print on December 3, 2014, on page A1 of the New York edition with the headline: Rewriting War, Japanese Right Goes on Attack. Order Reprints| Today's Paper|Subscribe

http://www.jiji.com/jc/c?g=pol_30&k=2014120300365

河野談話見直し狙う=米紙、「歴史修正主義」を批判

【ニューヨーク時事】米紙ニューヨーク・タイムズ(電子版)は2日、従軍慰安婦に関する記事取り消しをめぐる日本国内の「朝日新聞攻撃」を取り上げ、この風潮は歴史修正主義者を大胆にしており、安倍晋三首相らは慰安婦問題で謝罪した1993年の河野洋平官房長官談話を見直すチャンスだと捉えていると批判的に報じた。

同紙は、慰安婦の記事を書いた元朝日新聞記者とその家族や勤務先が脅迫の対象になっていると指摘。「彼ら(歴史修正主義者)は歴史否定のため脅迫を活用し、われわれを沈黙させたがっている」との元記者の話を伝えた。

ニューヨーク・タイムズは「日本軍が韓国で女性を拉致したという証拠はほとんどない」と認めつつ、「しかし歴史修正主義者はそれをもって、彼女たちが捕らわれの性奴隷だったことを否定し、金もうけ目的の売春婦だったと主張している」と指摘。多くの元慰安婦の証言があるにもかかわらず、日本の右翼は、朝日報道が国際的非難を生んだと批判しているとした。

同紙は慰安婦問題で日本に厳しい論説をしばしば載せており、朝日新聞による8月の記事取り消し後もその論調は全く変わっていない。(2014/12/03-12:25)

Rewriting the War, Japanese Right Attacks a Newspaper

By MARTIN FACKLERDEC. 2, 2014

Photo

Takashi Uemura, a former journalist, is under attack for his reporting on “comfort women.” Credit Ko Sasaki for The New York Times

Continue reading the main storyContinue reading the main storyShare This Page

Continue reading the main story

SAPPORO, Japan — Takashi Uemura was 33 when he wrote the article that would make his career. Then an investigative reporter for The Asahi Shimbun, Japan’s second-largest newspaper, he examined whether the Imperial Army had forced women to work in military brothels during World War II. His report, under the headline “Remembering Still Brings Tears,” was one of the first to tell the story of a former “comfort woman” from Korea.

Fast-forward a quarter century, and that article has made Mr. Uemura, now 56 and retired from journalism, a target of Japan’s political right. Tabloids brand him a traitor for disseminating “Korean lies” that they say were part of a smear campaign aimed at settling old scores with Japan. Threats of violence, Mr. Uemura says, have cost him one university teaching job and could soon rob him of a second. Ultranationalists have even gone after his children, posting Internet messages urging people to drive his teenage daughter to suicide.

The threats are part of a broad, vitriolic assault by the right-wing news media and politicians here on The Asahi, which has long been the newspaper that Japanese conservatives love to hate. The battle is also the most recent salvo in a long-raging dispute over Japan’s culpability for its wartime behavior that has flared under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s right-leaning government.

This latest campaign, however, has gone beyond anything postwar Japan has seen before, with nationalist politicians, including Mr. Abe himself, unleashing a torrent of abuse that has cowed one of the last strongholds of progressive political influence in Japan. It has also emboldened revisionists calling for a reconsideration of the government’s 1993 apology for the wartime coercion of women into prostitution.

“They are using intimidation as a way to deny history,” said Mr. Uemura, who spoke with a pleading urgency and came to an interview in this northern city with stacks of papers to defend himself. “They want to bully us into silence.”

“The War on The Asahi,” as commentators have called it, began in August when the newspaper bowed to public criticism and retracted at least a dozen articles published in the 1980s and early ’90s. Those articles cited a former soldier, Seiji Yoshida, who claimed to have helped abduct Korean women for the military brothels. Mr. Yoshida was discredited two decades ago, but the Japanese right pounced on The Asahi’s gesture and called for a boycott to drive the 135-year-old newspaper out of business.

Speaking to a parliamentary committee in October, Mr. Abe said The Asahi’s “mistaken reporting had caused many people injury, sorrow, pain and anger. It wounded Japan’s image.”

With elections this month, analysts say conservatives are trying to hobble the nation’s leading left-of-center newspaper. The Asahi has long supported greater atonement for Japan’s wartime militarism and has opposed Mr. Abe on other issues. But it is increasingly isolated as the nation’s liberal opposition remains in disarray after a crushing defeat at the polls two years ago.

Continue reading the main story

Mr. Abe and his political allies have also seized on The Asahi’s woes as a long-awaited chance to go after bigger game: the now internationally accepted view that the Japanese military coerced tens of thousands of Korean and other foreign women into sexual slavery during the war.

Most mainstream historians agree that the Imperial Army treated women in conquered territories as spoils of battle, rounding them up to work in a system of military-run brothels known as comfort stations that stretched from China to the South Pacific. Many were deceived with offers of jobs in factories and hospitals and then forced to provide sex for imperial soldiers in the comfort stations. In Southeast Asia, there is evidence that Japanese soldiers simply kidnapped women to work in the brothels.

Among the women who have come forward to say they were forced to have sex with soldiers are Chinese, Koreans and Filipinos, as well as Dutch women captured in Indonesia, then a Dutch colony.

There is little evidence that the Japanese military abducted or was directly involved in entrapping women in Korea, which had been a Japanese colony for decades when the war began, although the women and activists who support them say the women were often deceived and forced to work against their will.

The revisionists, however, have seized on the lack of evidence of abductions to deny that any women were held captive in sexual slavery and to argue that the comfort women were simply camp-following prostitutes out to make good money.

For scholars of the comfort women issue, the surprise was not The Asahi’s conclusion that Mr. Yoshida had lied — the newspaper acknowledged in 1997 that it could not verify his account — but that it waited so long to issue a formal retraction. Employees at The Asahi said it finally acted because members of the Abe government had been using the articles to criticize its reporters, and it hoped to blunt the attacks by setting the record straight.

Instead, the move prompted a storm of denunciations and gave the revisionists a new opening to promote their version of history. They are also pressing a claim that has left foreign experts scratching their heads in disbelief: that The Asahi alone is to blame for persuading the world that the comfort women were victims of coercion.

Though dozens of women have come forward with testimony about their ordeals, the Japanese right contends it was The Asahi’s reporting that resulted in international condemnation of Japan, including a 2007 resolution by the United States House of Representatives calling on Japan to apologize for “one of the largest cases of human trafficking in the 20th century.”

Continue reading the main story

RECENT COMMENTS

Alan Attlee 2 hours ago

In 1937 the Japanese Army raped and murdered several hundred thousand people in NanJing. It was convenient to MacArthur to allow...

Justice 2 hours ago

This is the fact you cannot change that he spread the hoax, not the fact, and it's obvious that he has to pay it then.Also New York Times...

hedwig 2 hours ago

Please read the following article written by Mr. Michael Yon, a highly respected US author.//// quote ////There are growing, unsubstantiated...

SEE ALL COMMENTS WRITE A COMMENT

For conservatives, humbling The Asahi is also a way to advance their long-held agenda of erasing portrayals of Imperial Japan that they consider too negative and eventually overturning the 1993 apology to comfort women, analysts say. Many on the right have argued that Japan’s behavior was no worse than that of other World War II combatants, including the United States’ bombing of Japanese civilians.

Continue reading the main storyContinue reading the main storyContinue reading the main story

“The Asahi’s admission is a chance for the revisionist right to say: ‘See! We told you so!’ ” said Koichi Nakano, a political scientist at Sophia University in Tokyo. “Abe sees this as his chance to go after a historical issue that he believes has hurt Japan’s national honor.”

The Asahi’s conservative competitor, The Yomiuri Shimbun, the world’s highest-circulation newspaper, has capitalized on its rival’s troubles by distributing leaflets that highlight The Asahi’s mistakes in reporting on comfort women. Since August, The Asahi’s daily circulation has dropped by 230,797 to about seven million, according to the Japan Audit Bureau of Circulations.

Right-wing tabloids have gone further, singling out Mr. Uemura as a “fabricator of the comfort women” even though his article was not among those that The Asahi retracted.

Mr. Uemura said The Asahi had been too fearful to defend him, or even itself. In September, the newspaper’s top executives apologized on television and fired the chief editor.

CONTINUE READING THE MAIN STORY

198

COMMENTS

“Abe is using The Asahi’s problems to intimidate other media into self-censorship,” said Jiro Yamaguchi, a political scientist who helped organize a petition to support Mr. Uemura. “This is a new form of McCarthyism.”

Hokusei Gakuen University, a small Christian college where Mr. Uemura lectures on local culture and history, said it was reviewing his contract because of bomb threats by ultranationalists. On a recent afternoon, some of Mr. Uemura’s supporters gathered to hear a sermon warning against repeating the mistakes of the dark years before the war, when the nation trampled dissent.

Mr. Uemura did not attend, explaining that he was now reluctant to appear in public. “This is the right’s way of threatening other journalists into silence,” he said. “They don’t want to suffer the same fate that I have.”

A version of this article appears in print on December 3, 2014, on page A1 of the New York edition with the headline: Rewriting War, Japanese Right Goes on Attack. Order Reprints| Today's Paper|Subscribe

http://www.jiji.com/jc/c?g=pol_30&k=2014120300365

河野談話見直し狙う=米紙、「歴史修正主義」を批判

【ニューヨーク時事】米紙ニューヨーク・タイムズ(電子版)は2日、従軍慰安婦に関する記事取り消しをめぐる日本国内の「朝日新聞攻撃」を取り上げ、この風潮は歴史修正主義者を大胆にしており、安倍晋三首相らは慰安婦問題で謝罪した1993年の河野洋平官房長官談話を見直すチャンスだと捉えていると批判的に報じた。

同紙は、慰安婦の記事を書いた元朝日新聞記者とその家族や勤務先が脅迫の対象になっていると指摘。「彼ら(歴史修正主義者)は歴史否定のため脅迫を活用し、われわれを沈黙させたがっている」との元記者の話を伝えた。

ニューヨーク・タイムズは「日本軍が韓国で女性を拉致したという証拠はほとんどない」と認めつつ、「しかし歴史修正主義者はそれをもって、彼女たちが捕らわれの性奴隷だったことを否定し、金もうけ目的の売春婦だったと主張している」と指摘。多くの元慰安婦の証言があるにもかかわらず、日本の右翼は、朝日報道が国際的非難を生んだと批判しているとした。

同紙は慰安婦問題で日本に厳しい論説をしばしば載せており、朝日新聞による8月の記事取り消し後もその論調は全く変わっていない。(2014/12/03-12:25)

↧

kado lesson

↧

sado lesson

↧

sado lesson merry christmas

↧

↧

kado lesson

↧

sado lesson

↧

Korean military also operated "comfort women system"

http://m.blog.daum.net/_blog/_m/articleView.do?blogid=03aXq&articleno=15851915

한국군도 '위안부'운용했다????

黃薔(李相遠) | 2013.08.06 05:26 목록 크게

댓글쓰기

한국군도 '위안부'운용했다

[창간 2주년 발굴특종 ①] 일본군 종군 경험의 유산

02.02.22 15:16l최종 업데이트 02.02.26 21:51l

김당(dangk)

Korean military also operated "comfort women system"

[anniversary excavation scoop, launched 2 ①]

heritage of the Japanese military veteran status

한국전쟁 기간[1951∼1954년] 3∼4개 중대 규모 운영…연간 최소 20여만 병력 '위안'

흔히 전쟁이 나면 여성들은 남성들에 비해 고통을 한 가지 더 겪는 것이 보통이다. 이는 다름아닌 '성적 유린'인데, 피아 군인을 가릴 것 없이 자행되는 것이 보통이다. 이같은 여성들의 피해사례는 동서고금의 전쟁사 곳곳에 기록돼 있다.

흔히 '위안부'라면 일제하 구 일본군들이 조선(한국)여성들을 강제로 끌고가 중국, 남양군도 등에서 성적 노리개로 부린 것으로만 생각하기 쉽다. 그러나 한국전쟁 당시 한국군도 병사들의 사기진작 차원에서 '위안부'를 운용했다는 주장이 제기돼 충격을 던지고 있다.

당시 서울, 강릉 등지의 군부대에서는 중대단위로 '위안부대'를 편성, 운용했는데 병사들은 '위안 대가'로 티킷이나 현금을 사용한 것으로 드러났다.

<오마이뉴스>는 우리 현대사에서 묻혀진 역사의 진실을 밝힌다는 차원에서 전문학자의 연구결과와 김당 편집위원의 취재를 토대로 4회 정도의 관련기획물을 실을 예정이다.-<편집자 주>

▲ 위안소 앞에 줄지어 선 일본군 병사들. 예비역 장성들의 회고록에 따르면 한국전쟁 당시 국군 장병들도 24인용 야전막사니 분대천막 앞에서 이처럼 줄을 서서 위안대를 이용했다. 한국전쟁 당시 국군이 군 위안소를 두고 위안부 제도를 운영했다는 주장이 학계에서 처음으로 공식 제기되었다. 6·25 전쟁 당시 국군이 위안소를 두고 장병들이 이용케 했다는 주장은 그 동안 몇몇 예비역 장군의 회고록과 참전자들의 증언에 의해서도 뒷받침되어 왔다.

그러나 군 당국이 편찬한 공식기록(전사) 등을 근거로 한국군이 위안대를 설치·운영했다는 주장이 제기된 것은 이번이 처음이다. 또 이를 계기로 당시 위안부 피해자들의 증언과 진상 규명운동이 전개될 경우, 지난 90년대 일본군 종군위안부 문제가 처음 제기된 때와 유사한 파문도 예상된다.

김귀옥 박사(경남대 북한전문대학원 객원교수·사회학)는 2월23일 일본 교토 리츠메이칸(立命館)대학에서 열리는 제5회 '동아시아 평화와 인권 국제심포지움'에서 이런 내용을 담은 '한국전쟁과 여성ː군 위안부와 군 위안소를 중심으로'라는 제목의 논문을 발표한다(관련 인터뷰 기사 송고 예정).

김박사의 논문은 한국군(한국전쟁) 위안부 문제라는 사안의 특성상 일본 언론들과 재일본조선인총련합회(총련)계 언론의 큰 관심을 끌 것으로 보여 귀추가 주목된다.

"사기 앙양과 전투력 손실 방지를 위한 필요악"

현재까지 발굴된 한국전쟁 당시 군 위안부 제도의 실체를 보여주는 유일한 공식자료는 육군본부가 지난 1956년에 편찬한 <후방전사(인사편)>에 실린 군 위안대 관련 기록이다.

김박사는 <후방전사> 기록과 예비역 장성들의 회고록, 그리고 관계자 증언 등을 토대로 당시 국군은 직접 설치한 고정식 위안소와 이동식 위안소 그리고 사창(私娼)의 직업여성들을 이용하는 세 가지 방식으로 위안부 제도를 운영했다고 주장한다. 우선 <후방전사(인사편)>의 '제3장 1절 3항 특수위안활동 사항'기록을 보면 군 위안대 설치 목적은 다음과 같다.

"표면화한 사리(事理)만을 가지고 간단히 국가시책에 역행하는 모순된 활동이라고 단안(斷案)하면 별문제이겠지만 실질적으로 사기앙양은 물론 전쟁사실에 따르는 피할 수 없는 폐단을 미연에 방지할 수 있을 뿐 아니라 장기간 교대 없는 전투로 인하여 후방 내왕(來往)이 없으니만치 이성에 대한 동경에서 야기되는 생리작용으로 인한 성격의 변화 등으로 우울증 및 기타 지장을 초래함을 예방하기 위하여 본(本) 특수위안대를 설치하게 되었다."

당시 군은 위안부들을 '특수위안대(特殊慰安隊)'라는 부대 형식으로 편제해 운영했음을 알 수 있다. <후방전사> 제3장의 '특수위안활동 사항'에는 흔히 '딴따라'라고 부르는 군예대(軍藝隊) 활동도 포함된다.

따라서 '특수위안대'는 군예대를 지칭하는 것이 아니냐는 이론도 있을 수 있다. 그러나 <후방전사>는 군예대의 활동을 '위문 공연(慰問 公演)'이라고 표현하는 반면에 특수위안대의 활동은 '위안(慰安)'이라고 용어를 구분해 사용하고 있다. 결국 여기서 '특수위안'은 여성의 성(性)적 서비스를 뜻함을 어렵지 않게 알 수 있다.

흥미로운 사실은 전사(戰史)에서 위안대 운영이 "국가시책에 역행하는 모순된 활동"임을 인정한 대목이다. 이는 일제시대에 설치된 공창(公娼)이 1948년 2월 미군정청의 공창폐지령 발효로 폐쇄되었음에도 국가를 수호하는 군이 자체적으로 사실상의 공창(군 위안대)을 운영하는 모순된 활동, 즉 범법행위를 자행했음을 의미한다.

따라서 <후방전사>는 군이 한국전쟁 당시 위안부 제도를 전쟁의 장기화에 따른 전투력 손실 방지와 사기 앙양을 위해 불가피한 일종의 '필요악'으로 간주했음을 드러내고 있는 것이다.

결국 한국군 위안대는 그 동원방식이나 운영기간 및 규모 면에서 일본군 종군위안부 제도와 근본적인 차이점이 있음에도 불구하고, 그 설치 목적이나 운영 방식 면에서는 비슷함을 보여준다. 이는 또 당시 한국군 수뇌부의 상당수가 일본군 출신이었음을 감안할 때 시사하는 바 크다. 일본군에서 위안부 제도를 경험한 군 수뇌부가 한국전쟁 기간에 위안부 제도를 주도적으로 도입한 것은 어쩌면 자연스런 경험의 산물이기 때문이다.

그런데 <후방전사>에 따르면 위안대를 설치한 시기는 불분명하다. 다만 "동란(動亂)중 (위안대) 활동상황을 연도별로 보면 큰 차이가 없었으며 전쟁행위와 더불어 불가분의 관계를 가진 것이라고 아니할 수 없다"고 돼 있어 전쟁 이후 설치된 것임을 짐작케 한다.

김귀옥 박사는 관련 자료와 관계자들의 증언을 토대로 설치 시기를 1951년으로 추정한다. 반면에 <후방전사>는 "휴전에 따라 이러한 시설의 설치목적이 해소됨에 이르러 공창(公娼) 폐지의 조류에 순명(順命)하여 단기 4287(서기 1954)년 3월 이를 일제히 폐쇄하였다"고 그 폐쇄 시기를 분명히 밝히고 있다.

서울 강릉 춘천 원주 속초 등 7개소 설치 운영

한편 <후방전사> 기록에 따르면 위안대가 설치된 장소는 △서울지구 3개 소대 △강릉지구 1개 소대 △기타 춘천 원주 속초 등지로 총 7개소에 이른다. 그러나 위안대 규모에 대해서는 <후방전사> 내에서도 앞뒤의 기록이 달라 정확한 그 규모를 산정하기가 어렵다.

이를테면 <후방전사>의 일부 기록(148쪽)에는 위안대 규모가 △서울지구 제1소대 19명 △강릉 제2소대 31명 △제8소대 8명 △강릉 제1소대 21명 등 총 79명으로 돼 있다.

그러나 같은 책의 '특수위안대 실적통계표'(150쪽)에는 위안부 수가 △서울 제1소대 19명 △서울 제2소대 27명 △서울 제3소대 13명 △강릉 제1소대 30명 등 총 89명으로 돼 있다.

따라서 전후 맥락으로 볼 때 전자의 기록은 오기(誤記)이고 후자의 '실적 통계표'가 정확한 것으로 추정된다. 물론 이 통계도 기타(춘천 원주 속초 등지) 지역 위안대는 포함하지 않고 있다. 아무튼 기록을 토대로 당시 위안소 소재지와 규모를 <표>로 정리하면 다음과 같다.

<표 1> 한국군 위안대 설치 장소와 규모 군에 위안대를 설치한 주체가 누구인지는 <후방전사>에서 찾아볼 수 없다. 그러나 군이 위안대 설치 및 운영을 주도한 사실은 <후방전사>의 다음과 같은 대목이나 예비역 장성들의 회고록에서 미루어 짐작할 수 있다.

"일선 부대의 요청에 의하여 출동위안(出動慰安)을 행하며 소재지에서도 출입하는 장병에 대하여 위안행위에 당하였다.(……) 한편 위안부는 1주에 2회 군무관(軍務官)의 협조로 군의관의 엄격한 검진을 받고 성병에 대하여는 철저한 대책을 강구하였다."(<후방전사>)

이는 당시 군이 군인들이 위안소를 찾아와 이용하는 고정식 위안소뿐 아니라 위안대가 위안을 위해 부대를 찾아가는 이동식 위안소도 운영했음을 입증하는 대목이다. 또 군의(軍醫)가 직접 위안부를 상대로 주 1회 성병검진을 실시한 점이나 장교를 상대하는 여성과 병사를 상대하는 여성이 따로 있었다는 점 등은 한국군 위안부 제도가 과거 일본군 종군위안부 운영방식을 그대로 답습했음을 의미한다.

주월(駐越) 한국군 사령관을 지낸 채명신 장군(예비역 육군 중장)은 자신의 회고록 <사선을 넘고넘어>(1994년)에서 <후방전사>의 기록과는 달리 소대 규모가 아닌 중대 규모로 위안대를 운용했다고 적고 있다. 이는 채명신 장군이 서울지구의 3개 소대 위안부 인력을 1개 중대 규모로 계산한 결과일 수 있다. 어쨌건 채장군에 따르면 당시 위안부 규모는 180∼240명으로 추정된다.

"당시 우리 육군은 사기 진작을 위해 60여명을 1개 중대로 하는 위안부대를 서너 개 운용하고 있었다. 때문에 예비부대로 빠지기만 하면 사단 요청에 의해 모든 부대는 위안부대를 이용할 수 있었다. 그러니 5연대도 예외는 아니었고, 예비대로 빠지기도 전부터 장병들의 화제는 모두 위안부대 건이었다."(이하 밑줄은 필자 강조)

▲ <후방전사>에 실려있는 단기 4285년(서기 1952년)의 '특수위안대 실적통계표'. 89명의 위안부가 연간 20여만명의 군인을 '위안'했음을 보여준다. 그렇다면 한국전쟁 기간에 군이 설치한 이 '특수위안대'의 '위안'활동 실적은 얼마나 될까. 그것을 가늠할 수 있는 유일한 근거자료는 바로 <후방전사>(150쪽)에 실린 '특수위안부 실적통계표'이다. 단기 4285년도이니 곧 1952년도 1년간의 '위안'실적이다. 다른 해의 실적도 이와 비슷하다고 기록되어 있다.

아무튼 이 통계표에 따르면, 1952년 당시 '특수위안대'에 편성된 위안부는 89명이고, 이들로부터 '위안'을 받은 군인은 연간 20만명이 넘는 것으로 집계되었다. 다만 이 실적이 실적통계표에 적시한 4곳(서울 제1, 2, 3소대·강릉 제1소대)에 출입한 군인들의 통계인지, 위안대가 현지부대로 '출동위안'한 군인들의 통계까지 포함한 것인지는 불명확하다.

▲ <표 2> 김귀옥 박사가 수정한 1952년 특수위안대 실적통계표

'위안대'는 예비대 병력의 '제5종 보급품'

전선에서 전투를 마치고 후방으로 교대된 예비부대 병력이 위안부를 이용할 수 있었다는 사실은 다른 장군들의 회고록에서도 일치하는 대목이다. 차규헌 장군(예비역 육군 대장) 또한 자신의 회고록 <전투>(1985년)에서 예비대 시절에 겪은 이동식 군 위안소 제도를 이렇게 회상하고 있다.

"(1952년) 3월 중순의 기후는 봄을 시샘할 듯 쌀쌀했다.(……) 잔적을 완전히 소탕한 후 예비대가 되어 부대정비를 실시하고 있을 때 사단 휼병부(恤兵部)로부터 장병을 위문하러 여자위안대가 부대 숙영지 부근에 도착하였다는 통보가 있었다. 중대 인사계 보고에 의하면 이들은 24인용 야전천막에 합판과 우의로 칸막이를 한 야전침실에 수용되었다고 하며 다른 중대병사들은 열을 서면서까지 많이 이용했다고 하였다."

▲ 김희오 장군(예비역 소장)의 회고록 <인간의 향기>. 34년간의 군 생활에서 한국전쟁 당시 처음 본 공개적 군 위안소 운영 사례에 대해 '영원히 찜찜한 기억'으로 기록하고 있다. 한편 김희오 장군(예비역 육군 소장) 또한 '이동식'이긴 하지만 이와는 조금 다른 각도에서 위안부 제도를 기억하고 있다.

김장군은 군에서 직접 위안소를 설치 운영한 것이라기보다는 연대 간부들이 당시 사창가였던 '종3'(종로3가)에서 거금을 주고 위안부로 데려온 것으로 기억한다. 김장군은 자신의 자서전 <인간의 향기>(2000년)에서 그 대목을 이렇게 회고하고 있다.

"(중부전선) 수도고지 전투도 잊혀지고 도망병 발생도 진정되어 갔다. 이제 FTX(야전훈련)에 본격 돌입하기 위해 소화기 및 장비 점검, 보급품 정비 등이 한창 진행되는 어느 날 아침이었다. 연대1과에서 중대별 제5종 보급품(군 보급품은 1∼4종밖에 없었음) 수령지시가 있어 가 보았더니 우리 중대에도 주간 8시간 제한으로 6명의 위안부가 배정되어 왔다.(……) 그러나 나는 백주에 많은 사람이 오가는 가운데 줄을 서서 분대천막을 이용하는 것이라던가 또 도덕적으로나 양심상 어정쩡하기도 해서 썩 내키지가 않았다. 먼저 소대에 2명이 할당되고 그중 1명이 먼저 소대장 천막으로 배정되어 왔다. 나는 출신환경 등 몇 마디 대화만 나누고 별로 도와줄 방법이 없어 그 동안 모아 놓았던 건빵 한 보따리를 싸서 선임하사관에게 인계하였다."

▲ 김희오 장군 두 장군의 증언에 따르면 군 부대에 소위 '제5종 보급품'이라는 이름으로 위안부들이 배정되어 왔고 24인용 야전천막이 위안소로 가설(차규헌 장군)되거나 분대 막사를 위안소로 대용(김희오 장군)하였다.

위안대가 '제5종 보급품'취급을 받은 것은 일본군 종군위안부가 '천황의 하사품'이나 '군수품'으로 취급받은 점과 일맥상통한다. 또 병사들이 줄을 서면서까지 많이 이용한 것이나 소대장 천막으로 먼저 배정된 후에 병사들에게 배정된 점 등도 일본군 종군위안부 피해자들이 증언하는 위안소의 풍경과 닮은꼴이다.

운영 방식은 증언에 따라 조금 다르다. 채명신 장군에 따르면 전선에서의 위안부대 출입은 '티켓제'로 운용토록 하였다. 그런데 아무에게나 티켓이 주어지는 것 아니었다. 전쟁터에서 용감하게 싸워 공을 세운 순서대로 나눠주었다. 또 공훈의 정도에 따라 티켓의 숫자가 달라졌다고 한다. 이는 군인들이 군표나 현금을 주고 이용했던 일본군 위안소와는 차이가 있다.

오히려 이것은 홋카이도나 사할린 지역에 강제 연행한 조선인 노동자와 일본인 노동자들을 상대로 회사에서 마련한 위안시설에서 일한 '산업위안부'제도와 닮은꼴이다. 일본이 저지른 대표적인 전쟁범죄인 종군위안부 문제에 가려 산업위안부 문제는 잘 드러나지 않았다.

그러나 일본 군수기업들은 노동자들에게 일종의 '성과급'으로 위안소를 이용할 수 있는 티켓을 제공하는 등 노동자를 통제하는 데 위안소 제도를 이용한 것으로 드러나고 있다. 결국 이런 사실들을 종합하면 한국전쟁 기간의 군 위안부 제도는 '일본군 종군위안부 제도의 잔재'라는 결론에 도달하게 된다.

"부끄러운 일본군 위안부 제도의 잔재"

그 때문인지 회고록에 군 위안부 제도를 기록한 장군들은 하나같이 위안소 운영의 타당성에 대한 의문과 함께 전쟁의 아픔, 그리고 절대빈곤의 참상을 지적한다.

▲ 한국전쟁 당시 연대장으로 복무한 채명신 장군(주월 한국군사령관)은 "군 위안부 제도는 장병들의 사기 진작과 성병 예방을 위해 도입한 '군부의 치부'이지만 당시 사회에 만연한 사창(私娼)을 군에 흡수해 인권을 보호한 측면도 있다"고 주장했다. 채명신 장군은 자신이 회고록에 기록한 한국전쟁 당시 겪은 군 위안부 제도에 대해 "드러내고 싶지 않은 군부의 치부이지만 움직일 수 없는 사실을 기록한 것"이라고 말했다. 그러면서도 채장군은 당시의 암울한 현실과 시대상황을 예로 들어 불가피성을 역설했다.

"당시는 전쟁이 장기화함에 따라 많은 젊은 여자들이 생계를 위해 미군 부대에서 몸을 팔고 전선 근처에까지 밀려드는 시절이었다. 당연히 사창에는 성병이 만연했고 사창을 방치할 경우 성병으로 인한 전투력 손실도 우려되었다. 따라서 군에서 장병들의 사기 진작과 전투력 손실 예방을 위해서 위안대를 편성해 군의관의 성병검진을 거쳐 장병들이 이용케 한 것이다. 그러나 어찌 보면 (창녀들을 군의 위안대에 흡수함으로써) 당시 사회의 필요악으로서 인권 사각지대에 방치된 많은 사창가 여자들의 인권을 보호한 측면도 있다."

그러나 당시 연대장이었던 채장군은 군 위안부 제도를 기획한 군 수뇌부의 주체가 누구인지에 대해서는 "잘 모르겠다"고 답했다. 또 채장군은 위안대의 규모에 대해서도 "명칭 상으로는 부대(특수위안대)이지만 부대 편제표에 의해 편성된 것이 아니기 때문에 위안부나 사창의 사정(수요공급)에 따라 위안대 규모가 그때그때 달라 정확한 인원을 산출하기가 어려웠을 것이다"고 지적했다.

"소대장님 티킷 한 장 더 얻을 수 없나요?" ....우리 5연대에서는 '위안부대'를 이용하는 데 몇 가지 규칙을 만들었다. 위안부대 출입은 티킷제로 운용토록 하였다. 그런데 아무에게나 티킷이 주어지는 건 아니다. 전쟁터에서 용감하게 싸워 공을 세운 순서대로 나눠준다. 물론 훈장을 받았다면 당연히 우선권이 있어 부러움의 대상이다.

"5연대는 무조건 계급에 관계없이 훈장을 많이 탄 사람부터 순서대로 위안부를 상대할 수 있다."

내가 이런 규칙을 만들자 부대 내에선 한바탕 입씨름이 벌어졌다.

"이제 너희는 모두 내 동생이다. 알았나?"

"잠시만 기다려라. 곧 내가 너희들에게 등정기를 발표할테니…. 기대하시라."

모든 입과 귀가 위안부대로 쏠려 있었다. 용감한 박판도 중사도 규정대로 두 장의 티킷을 받게 되었고, 첫 번째로 위안소에 가게 되었다.

난 당시 연대장이었으니 이 얘긴 후일 대대장을 통해 전해 들었다. 그런데 박중사는 숫총각이라 위안부 상대하는 것을 완강히 거부했다 한다. 그리곤 티킷도 다른 전우에게 주려 하는 걸 규칙이라 안된다며, 분대원들이 억지로 떠메곤 위안부대의 천막 속에다 집어넣었다 한다.

모든 분대원들은 천막 안을 들여다보면서 역사적 사태(?)를 지켜보았는데, 아뿔싸 순진한 박판도 총각은 여자가 바지를 벗기려 하자 "싫다"며 도망가질 않나, 억지로 벗기곤 강행하려 하자 결사적으로 피하질 않나, 밖에서 지켜보는 분대원들에게 한바탕 웃음만 안겨주고 있었다.

그러나 워낙 좁은 곳이라 결국은 여자한테 붙잡혔는데 상대가 숫총각이란 걸 안 여자가 장난삼아 그의 물건을 만지면서 "애걔, 요만한 걸 가지고 왔어?"하며 놀리자, 끝끝내 그는 총(?) 한방 못쏴보고 얼굴만 빨개가지곤 도망쳐 나왔다는 거였다.

분대원들은 자신의 분대장에게 치욕의 여름(夏)을 남기지 않으려, 그날 밤 철저한 강의와 사례를 들려주어 결국 박판도 중사를 설득시켰다. 다음날 재시도 끝에 박판도 중사는 결국 성공한다.

그런데 문제는 다음부터다. 한번 위안부대를 다녀온 박중사가 완전히 맛을 들인 것이다.

"저…, 소대장님. 저…, 티킷 한 장 더 얻을 수 없나요?"

이 지경까지 되어 내게 보고가 올라오니 난 웃음을 터뜨리지 않을 수 없었다.

"허, 그놈 참. 그래 대대장이 알아서 두어 장 더 집어줘…. 하하하…."

그때부터 난 왠지 마음에 걸렸다. 순진한 녀석이 전투만 알다가 어느날 갑자기 인생의 어떤 새로운 면을 알게 되었다면….

<채명신 회고록 '사선을 넘고 넘어'> (267~269쪽에서 인용)

육군본부의 공식기록인 <후방전사>의 '특수위안대 실적통계표'(1952년)에 따르더라도 당시 위안대를 이용한 장병은 적게 잡아도 연간 20만명을 넘는다. 또 "위안대를 이용할 수 있는 예비대로 빠지기도 전부터 장병들의 화제는 모두 위안부대 건이었다"는 채장군의 증언에서 보듯, 당시 한국전쟁에 참전했던 모든 군인들은 군이 설치·운용한 '특수위안대'의 존재를 알고 있었다.

바로 그 '공공연한 비밀'이 50년만에 뒤늦게 불거진 것은, 이 드러내고 싶지 않은 군부의 치부가 일본군 위안부 제도의 찌꺼기이기 때문인지도 모른다.

물론 한국군 위안대는 동원방식이나 기간 그리고 규모 등에서 일본군 종군위안부 제도와 본질적인 차이점이 있다. 그러나 상당 부분 일본군 종군위안부 제도와 유사한 방식으로 운용된 것 또한 사실이다(아래 <표 3> 참조).

<표 3> 일본군·한국군 위안부 제도의 유사점과 차이점 우선 사기 앙양과 전투력 손실 예방을 내세운 설치 목적부터가 유사하다. 또 병사들이 군대천막 앞에서 줄을 서서 이용하고 군의관이 성병검진을 하는 이용·관리 풍경도 흡사하다. 또 일본군의 군표 대신에 티켓과 같은 대가가 지불된 거래형식으로 운용되기도 했다.

이는 목격자들의 증언으로도 뒷받침된다. 한국전쟁 당시 이 희한한 제도를 처음 겪은 김희오 장군은 처음 위안대를 목격한 순간에 직감적으로 "이는 과거 일본군 내 종군 경험이 있는 일부 간부들이 부하 사기앙양을 위한 발상에서 비롯된 것이구나"하는 생각이 들었다고 한다. 그래서 김장군은 34년간 군 생활에서 처음 본 공개적인 군 위안소 운영 사례에 대해 그 당위성을 떠나 영원히 찜찜한 기억으로 각인되어 있다고 기억한다.

이 '찜찜한 기억'은 바로 8·15 해방과 48년 정부 수립 이후 초기 국가 및 군부 형성에 깊은 영향을 준 친일파 청산문제와 맞닿아 있는 것이다. 이를테면 합참의장은 1대 이형근 의장부터 14대 노재현 의장까지, 육군 참모총장은 1대 이응준 총장부터 21대 이세호 총장에 이르기까지 일제 군경력자들이 독식했다는 점을 미루어볼 때, 한국전쟁 당시 위안부 문제는 미청산된 친일파 문제와 직결되어 있음을 직감할 수 있는 것이다.

김귀옥 박사는 "한국전쟁 군 위안부 문제는 일본군 위안부 제도의 불행한 자식이라고 할 수 있다"면서 "이 문제도 (일본군 위안부 문제처럼) 피해 여성과 사회 단체 그리고 학계가 연대하여 풀어내야 할 우리의 과거 청산 문제의 하나"임을 강조했다.

한국군도 '위안부'운용했다????

黃薔(李相遠) | 2013.08.06 05:26 목록 크게

댓글쓰기

한국군도 '위안부'운용했다

[창간 2주년 발굴특종 ①] 일본군 종군 경험의 유산

02.02.22 15:16l최종 업데이트 02.02.26 21:51l

김당(dangk)

Korean military also operated "comfort women system"

[anniversary excavation scoop, launched 2 ①]

heritage of the Japanese military veteran status

한국전쟁 기간[1951∼1954년] 3∼4개 중대 규모 운영…연간 최소 20여만 병력 '위안'

흔히 전쟁이 나면 여성들은 남성들에 비해 고통을 한 가지 더 겪는 것이 보통이다. 이는 다름아닌 '성적 유린'인데, 피아 군인을 가릴 것 없이 자행되는 것이 보통이다. 이같은 여성들의 피해사례는 동서고금의 전쟁사 곳곳에 기록돼 있다.

흔히 '위안부'라면 일제하 구 일본군들이 조선(한국)여성들을 강제로 끌고가 중국, 남양군도 등에서 성적 노리개로 부린 것으로만 생각하기 쉽다. 그러나 한국전쟁 당시 한국군도 병사들의 사기진작 차원에서 '위안부'를 운용했다는 주장이 제기돼 충격을 던지고 있다.

당시 서울, 강릉 등지의 군부대에서는 중대단위로 '위안부대'를 편성, 운용했는데 병사들은 '위안 대가'로 티킷이나 현금을 사용한 것으로 드러났다.

<오마이뉴스>는 우리 현대사에서 묻혀진 역사의 진실을 밝힌다는 차원에서 전문학자의 연구결과와 김당 편집위원의 취재를 토대로 4회 정도의 관련기획물을 실을 예정이다.-<편집자 주>

▲ 위안소 앞에 줄지어 선 일본군 병사들. 예비역 장성들의 회고록에 따르면 한국전쟁 당시 국군 장병들도 24인용 야전막사니 분대천막 앞에서 이처럼 줄을 서서 위안대를 이용했다. 한국전쟁 당시 국군이 군 위안소를 두고 위안부 제도를 운영했다는 주장이 학계에서 처음으로 공식 제기되었다. 6·25 전쟁 당시 국군이 위안소를 두고 장병들이 이용케 했다는 주장은 그 동안 몇몇 예비역 장군의 회고록과 참전자들의 증언에 의해서도 뒷받침되어 왔다.

그러나 군 당국이 편찬한 공식기록(전사) 등을 근거로 한국군이 위안대를 설치·운영했다는 주장이 제기된 것은 이번이 처음이다. 또 이를 계기로 당시 위안부 피해자들의 증언과 진상 규명운동이 전개될 경우, 지난 90년대 일본군 종군위안부 문제가 처음 제기된 때와 유사한 파문도 예상된다.

김귀옥 박사(경남대 북한전문대학원 객원교수·사회학)는 2월23일 일본 교토 리츠메이칸(立命館)대학에서 열리는 제5회 '동아시아 평화와 인권 국제심포지움'에서 이런 내용을 담은 '한국전쟁과 여성ː군 위안부와 군 위안소를 중심으로'라는 제목의 논문을 발표한다(관련 인터뷰 기사 송고 예정).

김박사의 논문은 한국군(한국전쟁) 위안부 문제라는 사안의 특성상 일본 언론들과 재일본조선인총련합회(총련)계 언론의 큰 관심을 끌 것으로 보여 귀추가 주목된다.

"사기 앙양과 전투력 손실 방지를 위한 필요악"

현재까지 발굴된 한국전쟁 당시 군 위안부 제도의 실체를 보여주는 유일한 공식자료는 육군본부가 지난 1956년에 편찬한 <후방전사(인사편)>에 실린 군 위안대 관련 기록이다.

김박사는 <후방전사> 기록과 예비역 장성들의 회고록, 그리고 관계자 증언 등을 토대로 당시 국군은 직접 설치한 고정식 위안소와 이동식 위안소 그리고 사창(私娼)의 직업여성들을 이용하는 세 가지 방식으로 위안부 제도를 운영했다고 주장한다. 우선 <후방전사(인사편)>의 '제3장 1절 3항 특수위안활동 사항'기록을 보면 군 위안대 설치 목적은 다음과 같다.

"표면화한 사리(事理)만을 가지고 간단히 국가시책에 역행하는 모순된 활동이라고 단안(斷案)하면 별문제이겠지만 실질적으로 사기앙양은 물론 전쟁사실에 따르는 피할 수 없는 폐단을 미연에 방지할 수 있을 뿐 아니라 장기간 교대 없는 전투로 인하여 후방 내왕(來往)이 없으니만치 이성에 대한 동경에서 야기되는 생리작용으로 인한 성격의 변화 등으로 우울증 및 기타 지장을 초래함을 예방하기 위하여 본(本) 특수위안대를 설치하게 되었다."

당시 군은 위안부들을 '특수위안대(特殊慰安隊)'라는 부대 형식으로 편제해 운영했음을 알 수 있다. <후방전사> 제3장의 '특수위안활동 사항'에는 흔히 '딴따라'라고 부르는 군예대(軍藝隊) 활동도 포함된다.

따라서 '특수위안대'는 군예대를 지칭하는 것이 아니냐는 이론도 있을 수 있다. 그러나 <후방전사>는 군예대의 활동을 '위문 공연(慰問 公演)'이라고 표현하는 반면에 특수위안대의 활동은 '위안(慰安)'이라고 용어를 구분해 사용하고 있다. 결국 여기서 '특수위안'은 여성의 성(性)적 서비스를 뜻함을 어렵지 않게 알 수 있다.

흥미로운 사실은 전사(戰史)에서 위안대 운영이 "국가시책에 역행하는 모순된 활동"임을 인정한 대목이다. 이는 일제시대에 설치된 공창(公娼)이 1948년 2월 미군정청의 공창폐지령 발효로 폐쇄되었음에도 국가를 수호하는 군이 자체적으로 사실상의 공창(군 위안대)을 운영하는 모순된 활동, 즉 범법행위를 자행했음을 의미한다.

따라서 <후방전사>는 군이 한국전쟁 당시 위안부 제도를 전쟁의 장기화에 따른 전투력 손실 방지와 사기 앙양을 위해 불가피한 일종의 '필요악'으로 간주했음을 드러내고 있는 것이다.

결국 한국군 위안대는 그 동원방식이나 운영기간 및 규모 면에서 일본군 종군위안부 제도와 근본적인 차이점이 있음에도 불구하고, 그 설치 목적이나 운영 방식 면에서는 비슷함을 보여준다. 이는 또 당시 한국군 수뇌부의 상당수가 일본군 출신이었음을 감안할 때 시사하는 바 크다. 일본군에서 위안부 제도를 경험한 군 수뇌부가 한국전쟁 기간에 위안부 제도를 주도적으로 도입한 것은 어쩌면 자연스런 경험의 산물이기 때문이다.

그런데 <후방전사>에 따르면 위안대를 설치한 시기는 불분명하다. 다만 "동란(動亂)중 (위안대) 활동상황을 연도별로 보면 큰 차이가 없었으며 전쟁행위와 더불어 불가분의 관계를 가진 것이라고 아니할 수 없다"고 돼 있어 전쟁 이후 설치된 것임을 짐작케 한다.

김귀옥 박사는 관련 자료와 관계자들의 증언을 토대로 설치 시기를 1951년으로 추정한다. 반면에 <후방전사>는 "휴전에 따라 이러한 시설의 설치목적이 해소됨에 이르러 공창(公娼) 폐지의 조류에 순명(順命)하여 단기 4287(서기 1954)년 3월 이를 일제히 폐쇄하였다"고 그 폐쇄 시기를 분명히 밝히고 있다.

서울 강릉 춘천 원주 속초 등 7개소 설치 운영

한편 <후방전사> 기록에 따르면 위안대가 설치된 장소는 △서울지구 3개 소대 △강릉지구 1개 소대 △기타 춘천 원주 속초 등지로 총 7개소에 이른다. 그러나 위안대 규모에 대해서는 <후방전사> 내에서도 앞뒤의 기록이 달라 정확한 그 규모를 산정하기가 어렵다.

이를테면 <후방전사>의 일부 기록(148쪽)에는 위안대 규모가 △서울지구 제1소대 19명 △강릉 제2소대 31명 △제8소대 8명 △강릉 제1소대 21명 등 총 79명으로 돼 있다.

그러나 같은 책의 '특수위안대 실적통계표'(150쪽)에는 위안부 수가 △서울 제1소대 19명 △서울 제2소대 27명 △서울 제3소대 13명 △강릉 제1소대 30명 등 총 89명으로 돼 있다.

따라서 전후 맥락으로 볼 때 전자의 기록은 오기(誤記)이고 후자의 '실적 통계표'가 정확한 것으로 추정된다. 물론 이 통계도 기타(춘천 원주 속초 등지) 지역 위안대는 포함하지 않고 있다. 아무튼 기록을 토대로 당시 위안소 소재지와 규모를 <표>로 정리하면 다음과 같다.

<표 1> 한국군 위안대 설치 장소와 규모 군에 위안대를 설치한 주체가 누구인지는 <후방전사>에서 찾아볼 수 없다. 그러나 군이 위안대 설치 및 운영을 주도한 사실은 <후방전사>의 다음과 같은 대목이나 예비역 장성들의 회고록에서 미루어 짐작할 수 있다.

"일선 부대의 요청에 의하여 출동위안(出動慰安)을 행하며 소재지에서도 출입하는 장병에 대하여 위안행위에 당하였다.(……) 한편 위안부는 1주에 2회 군무관(軍務官)의 협조로 군의관의 엄격한 검진을 받고 성병에 대하여는 철저한 대책을 강구하였다."(<후방전사>)

이는 당시 군이 군인들이 위안소를 찾아와 이용하는 고정식 위안소뿐 아니라 위안대가 위안을 위해 부대를 찾아가는 이동식 위안소도 운영했음을 입증하는 대목이다. 또 군의(軍醫)가 직접 위안부를 상대로 주 1회 성병검진을 실시한 점이나 장교를 상대하는 여성과 병사를 상대하는 여성이 따로 있었다는 점 등은 한국군 위안부 제도가 과거 일본군 종군위안부 운영방식을 그대로 답습했음을 의미한다.

주월(駐越) 한국군 사령관을 지낸 채명신 장군(예비역 육군 중장)은 자신의 회고록 <사선을 넘고넘어>(1994년)에서 <후방전사>의 기록과는 달리 소대 규모가 아닌 중대 규모로 위안대를 운용했다고 적고 있다. 이는 채명신 장군이 서울지구의 3개 소대 위안부 인력을 1개 중대 규모로 계산한 결과일 수 있다. 어쨌건 채장군에 따르면 당시 위안부 규모는 180∼240명으로 추정된다.

"당시 우리 육군은 사기 진작을 위해 60여명을 1개 중대로 하는 위안부대를 서너 개 운용하고 있었다. 때문에 예비부대로 빠지기만 하면 사단 요청에 의해 모든 부대는 위안부대를 이용할 수 있었다. 그러니 5연대도 예외는 아니었고, 예비대로 빠지기도 전부터 장병들의 화제는 모두 위안부대 건이었다."(이하 밑줄은 필자 강조)

▲ <후방전사>에 실려있는 단기 4285년(서기 1952년)의 '특수위안대 실적통계표'. 89명의 위안부가 연간 20여만명의 군인을 '위안'했음을 보여준다. 그렇다면 한국전쟁 기간에 군이 설치한 이 '특수위안대'의 '위안'활동 실적은 얼마나 될까. 그것을 가늠할 수 있는 유일한 근거자료는 바로 <후방전사>(150쪽)에 실린 '특수위안부 실적통계표'이다. 단기 4285년도이니 곧 1952년도 1년간의 '위안'실적이다. 다른 해의 실적도 이와 비슷하다고 기록되어 있다.

아무튼 이 통계표에 따르면, 1952년 당시 '특수위안대'에 편성된 위안부는 89명이고, 이들로부터 '위안'을 받은 군인은 연간 20만명이 넘는 것으로 집계되었다. 다만 이 실적이 실적통계표에 적시한 4곳(서울 제1, 2, 3소대·강릉 제1소대)에 출입한 군인들의 통계인지, 위안대가 현지부대로 '출동위안'한 군인들의 통계까지 포함한 것인지는 불명확하다.

▲ <표 2> 김귀옥 박사가 수정한 1952년 특수위안대 실적통계표

'위안대'는 예비대 병력의 '제5종 보급품'

전선에서 전투를 마치고 후방으로 교대된 예비부대 병력이 위안부를 이용할 수 있었다는 사실은 다른 장군들의 회고록에서도 일치하는 대목이다. 차규헌 장군(예비역 육군 대장) 또한 자신의 회고록 <전투>(1985년)에서 예비대 시절에 겪은 이동식 군 위안소 제도를 이렇게 회상하고 있다.

"(1952년) 3월 중순의 기후는 봄을 시샘할 듯 쌀쌀했다.(……) 잔적을 완전히 소탕한 후 예비대가 되어 부대정비를 실시하고 있을 때 사단 휼병부(恤兵部)로부터 장병을 위문하러 여자위안대가 부대 숙영지 부근에 도착하였다는 통보가 있었다. 중대 인사계 보고에 의하면 이들은 24인용 야전천막에 합판과 우의로 칸막이를 한 야전침실에 수용되었다고 하며 다른 중대병사들은 열을 서면서까지 많이 이용했다고 하였다."

▲ 김희오 장군(예비역 소장)의 회고록 <인간의 향기>. 34년간의 군 생활에서 한국전쟁 당시 처음 본 공개적 군 위안소 운영 사례에 대해 '영원히 찜찜한 기억'으로 기록하고 있다. 한편 김희오 장군(예비역 육군 소장) 또한 '이동식'이긴 하지만 이와는 조금 다른 각도에서 위안부 제도를 기억하고 있다.

김장군은 군에서 직접 위안소를 설치 운영한 것이라기보다는 연대 간부들이 당시 사창가였던 '종3'(종로3가)에서 거금을 주고 위안부로 데려온 것으로 기억한다. 김장군은 자신의 자서전 <인간의 향기>(2000년)에서 그 대목을 이렇게 회고하고 있다.

"(중부전선) 수도고지 전투도 잊혀지고 도망병 발생도 진정되어 갔다. 이제 FTX(야전훈련)에 본격 돌입하기 위해 소화기 및 장비 점검, 보급품 정비 등이 한창 진행되는 어느 날 아침이었다. 연대1과에서 중대별 제5종 보급품(군 보급품은 1∼4종밖에 없었음) 수령지시가 있어 가 보았더니 우리 중대에도 주간 8시간 제한으로 6명의 위안부가 배정되어 왔다.(……) 그러나 나는 백주에 많은 사람이 오가는 가운데 줄을 서서 분대천막을 이용하는 것이라던가 또 도덕적으로나 양심상 어정쩡하기도 해서 썩 내키지가 않았다. 먼저 소대에 2명이 할당되고 그중 1명이 먼저 소대장 천막으로 배정되어 왔다. 나는 출신환경 등 몇 마디 대화만 나누고 별로 도와줄 방법이 없어 그 동안 모아 놓았던 건빵 한 보따리를 싸서 선임하사관에게 인계하였다."

▲ 김희오 장군 두 장군의 증언에 따르면 군 부대에 소위 '제5종 보급품'이라는 이름으로 위안부들이 배정되어 왔고 24인용 야전천막이 위안소로 가설(차규헌 장군)되거나 분대 막사를 위안소로 대용(김희오 장군)하였다.

위안대가 '제5종 보급품'취급을 받은 것은 일본군 종군위안부가 '천황의 하사품'이나 '군수품'으로 취급받은 점과 일맥상통한다. 또 병사들이 줄을 서면서까지 많이 이용한 것이나 소대장 천막으로 먼저 배정된 후에 병사들에게 배정된 점 등도 일본군 종군위안부 피해자들이 증언하는 위안소의 풍경과 닮은꼴이다.

운영 방식은 증언에 따라 조금 다르다. 채명신 장군에 따르면 전선에서의 위안부대 출입은 '티켓제'로 운용토록 하였다. 그런데 아무에게나 티켓이 주어지는 것 아니었다. 전쟁터에서 용감하게 싸워 공을 세운 순서대로 나눠주었다. 또 공훈의 정도에 따라 티켓의 숫자가 달라졌다고 한다. 이는 군인들이 군표나 현금을 주고 이용했던 일본군 위안소와는 차이가 있다.

오히려 이것은 홋카이도나 사할린 지역에 강제 연행한 조선인 노동자와 일본인 노동자들을 상대로 회사에서 마련한 위안시설에서 일한 '산업위안부'제도와 닮은꼴이다. 일본이 저지른 대표적인 전쟁범죄인 종군위안부 문제에 가려 산업위안부 문제는 잘 드러나지 않았다.

그러나 일본 군수기업들은 노동자들에게 일종의 '성과급'으로 위안소를 이용할 수 있는 티켓을 제공하는 등 노동자를 통제하는 데 위안소 제도를 이용한 것으로 드러나고 있다. 결국 이런 사실들을 종합하면 한국전쟁 기간의 군 위안부 제도는 '일본군 종군위안부 제도의 잔재'라는 결론에 도달하게 된다.

"부끄러운 일본군 위안부 제도의 잔재"

그 때문인지 회고록에 군 위안부 제도를 기록한 장군들은 하나같이 위안소 운영의 타당성에 대한 의문과 함께 전쟁의 아픔, 그리고 절대빈곤의 참상을 지적한다.

▲ 한국전쟁 당시 연대장으로 복무한 채명신 장군(주월 한국군사령관)은 "군 위안부 제도는 장병들의 사기 진작과 성병 예방을 위해 도입한 '군부의 치부'이지만 당시 사회에 만연한 사창(私娼)을 군에 흡수해 인권을 보호한 측면도 있다"고 주장했다. 채명신 장군은 자신이 회고록에 기록한 한국전쟁 당시 겪은 군 위안부 제도에 대해 "드러내고 싶지 않은 군부의 치부이지만 움직일 수 없는 사실을 기록한 것"이라고 말했다. 그러면서도 채장군은 당시의 암울한 현실과 시대상황을 예로 들어 불가피성을 역설했다.

"당시는 전쟁이 장기화함에 따라 많은 젊은 여자들이 생계를 위해 미군 부대에서 몸을 팔고 전선 근처에까지 밀려드는 시절이었다. 당연히 사창에는 성병이 만연했고 사창을 방치할 경우 성병으로 인한 전투력 손실도 우려되었다. 따라서 군에서 장병들의 사기 진작과 전투력 손실 예방을 위해서 위안대를 편성해 군의관의 성병검진을 거쳐 장병들이 이용케 한 것이다. 그러나 어찌 보면 (창녀들을 군의 위안대에 흡수함으로써) 당시 사회의 필요악으로서 인권 사각지대에 방치된 많은 사창가 여자들의 인권을 보호한 측면도 있다."

그러나 당시 연대장이었던 채장군은 군 위안부 제도를 기획한 군 수뇌부의 주체가 누구인지에 대해서는 "잘 모르겠다"고 답했다. 또 채장군은 위안대의 규모에 대해서도 "명칭 상으로는 부대(특수위안대)이지만 부대 편제표에 의해 편성된 것이 아니기 때문에 위안부나 사창의 사정(수요공급)에 따라 위안대 규모가 그때그때 달라 정확한 인원을 산출하기가 어려웠을 것이다"고 지적했다.

"소대장님 티킷 한 장 더 얻을 수 없나요?" ....우리 5연대에서는 '위안부대'를 이용하는 데 몇 가지 규칙을 만들었다. 위안부대 출입은 티킷제로 운용토록 하였다. 그런데 아무에게나 티킷이 주어지는 건 아니다. 전쟁터에서 용감하게 싸워 공을 세운 순서대로 나눠준다. 물론 훈장을 받았다면 당연히 우선권이 있어 부러움의 대상이다.

"5연대는 무조건 계급에 관계없이 훈장을 많이 탄 사람부터 순서대로 위안부를 상대할 수 있다."

내가 이런 규칙을 만들자 부대 내에선 한바탕 입씨름이 벌어졌다.

"이제 너희는 모두 내 동생이다. 알았나?"

"잠시만 기다려라. 곧 내가 너희들에게 등정기를 발표할테니…. 기대하시라."

모든 입과 귀가 위안부대로 쏠려 있었다. 용감한 박판도 중사도 규정대로 두 장의 티킷을 받게 되었고, 첫 번째로 위안소에 가게 되었다.

난 당시 연대장이었으니 이 얘긴 후일 대대장을 통해 전해 들었다. 그런데 박중사는 숫총각이라 위안부 상대하는 것을 완강히 거부했다 한다. 그리곤 티킷도 다른 전우에게 주려 하는 걸 규칙이라 안된다며, 분대원들이 억지로 떠메곤 위안부대의 천막 속에다 집어넣었다 한다.

모든 분대원들은 천막 안을 들여다보면서 역사적 사태(?)를 지켜보았는데, 아뿔싸 순진한 박판도 총각은 여자가 바지를 벗기려 하자 "싫다"며 도망가질 않나, 억지로 벗기곤 강행하려 하자 결사적으로 피하질 않나, 밖에서 지켜보는 분대원들에게 한바탕 웃음만 안겨주고 있었다.

그러나 워낙 좁은 곳이라 결국은 여자한테 붙잡혔는데 상대가 숫총각이란 걸 안 여자가 장난삼아 그의 물건을 만지면서 "애걔, 요만한 걸 가지고 왔어?"하며 놀리자, 끝끝내 그는 총(?) 한방 못쏴보고 얼굴만 빨개가지곤 도망쳐 나왔다는 거였다.

분대원들은 자신의 분대장에게 치욕의 여름(夏)을 남기지 않으려, 그날 밤 철저한 강의와 사례를 들려주어 결국 박판도 중사를 설득시켰다. 다음날 재시도 끝에 박판도 중사는 결국 성공한다.

그런데 문제는 다음부터다. 한번 위안부대를 다녀온 박중사가 완전히 맛을 들인 것이다.

"저…, 소대장님. 저…, 티킷 한 장 더 얻을 수 없나요?"

이 지경까지 되어 내게 보고가 올라오니 난 웃음을 터뜨리지 않을 수 없었다.

"허, 그놈 참. 그래 대대장이 알아서 두어 장 더 집어줘…. 하하하…."

그때부터 난 왠지 마음에 걸렸다. 순진한 녀석이 전투만 알다가 어느날 갑자기 인생의 어떤 새로운 면을 알게 되었다면….

<채명신 회고록 '사선을 넘고 넘어'> (267~269쪽에서 인용)

육군본부의 공식기록인 <후방전사>의 '특수위안대 실적통계표'(1952년)에 따르더라도 당시 위안대를 이용한 장병은 적게 잡아도 연간 20만명을 넘는다. 또 "위안대를 이용할 수 있는 예비대로 빠지기도 전부터 장병들의 화제는 모두 위안부대 건이었다"는 채장군의 증언에서 보듯, 당시 한국전쟁에 참전했던 모든 군인들은 군이 설치·운용한 '특수위안대'의 존재를 알고 있었다.

바로 그 '공공연한 비밀'이 50년만에 뒤늦게 불거진 것은, 이 드러내고 싶지 않은 군부의 치부가 일본군 위안부 제도의 찌꺼기이기 때문인지도 모른다.

물론 한국군 위안대는 동원방식이나 기간 그리고 규모 등에서 일본군 종군위안부 제도와 본질적인 차이점이 있다. 그러나 상당 부분 일본군 종군위안부 제도와 유사한 방식으로 운용된 것 또한 사실이다(아래 <표 3> 참조).

<표 3> 일본군·한국군 위안부 제도의 유사점과 차이점 우선 사기 앙양과 전투력 손실 예방을 내세운 설치 목적부터가 유사하다. 또 병사들이 군대천막 앞에서 줄을 서서 이용하고 군의관이 성병검진을 하는 이용·관리 풍경도 흡사하다. 또 일본군의 군표 대신에 티켓과 같은 대가가 지불된 거래형식으로 운용되기도 했다.

이는 목격자들의 증언으로도 뒷받침된다. 한국전쟁 당시 이 희한한 제도를 처음 겪은 김희오 장군은 처음 위안대를 목격한 순간에 직감적으로 "이는 과거 일본군 내 종군 경험이 있는 일부 간부들이 부하 사기앙양을 위한 발상에서 비롯된 것이구나"하는 생각이 들었다고 한다. 그래서 김장군은 34년간 군 생활에서 처음 본 공개적인 군 위안소 운영 사례에 대해 그 당위성을 떠나 영원히 찜찜한 기억으로 각인되어 있다고 기억한다.

이 '찜찜한 기억'은 바로 8·15 해방과 48년 정부 수립 이후 초기 국가 및 군부 형성에 깊은 영향을 준 친일파 청산문제와 맞닿아 있는 것이다. 이를테면 합참의장은 1대 이형근 의장부터 14대 노재현 의장까지, 육군 참모총장은 1대 이응준 총장부터 21대 이세호 총장에 이르기까지 일제 군경력자들이 독식했다는 점을 미루어볼 때, 한국전쟁 당시 위안부 문제는 미청산된 친일파 문제와 직결되어 있음을 직감할 수 있는 것이다.

김귀옥 박사는 "한국전쟁 군 위안부 문제는 일본군 위안부 제도의 불행한 자식이라고 할 수 있다"면서 "이 문제도 (일본군 위안부 문제처럼) 피해 여성과 사회 단체 그리고 학계가 연대하여 풀어내야 할 우리의 과거 청산 문제의 하나"임을 강조했다.

↧

The Pope's Verdict on Japan's Comfort Women

http://nationalinterest.org/feature/the-popes-verdict-japans-comfort-women-11168

The Pope's Verdict on Japan's Comfort Women

"The Pope returned the Comfort Women discussion to where it belongs—which is to comfort the victims."

Mindy Kotler

August 31, 2014

Before his final mass in South Korea on August 18, Pope Francis met with seven elderly ladies who had been Comfort Women. As teenagers during World War II they were trafficked by Imperial Japan to be sex slaves. Military records on the operation of a comfort station show that the girls had to service not only soldiers and sailors, but also Japanese government and corporate officials.

The Pope bent down and clasped the frail hands of each woman. One offered him a butterfly pin, a symbol of their lost innocence, which the Pontiff immediately fastened to his vestments and wore throughout the service. Prior to the mass, he was handed a letter from the Dutch former Comfort Woman, Jan Ruff O’Herne, who at 92 could not travel from her home in Australia to meet him. She wanted him to know that before she was chosen by Japanese Army officers in her concentration camp on Java and raped in a Semarang military brothel, her dream was to become a nun.

The women received more than the Pope’s blessing. They received affirmation that their history was believed and their suffering real. Francis has championed the elimination of human trafficking and preached on the evils of sexual slavery. By a simple gesture, he included their experience with all victims caught up in sexual violence. He understands that rape is a weapon of subjugation and humiliation. Unlike Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe, the Pontiff does not rationalize the Comfort Women experience with “the 20th century was a century where many human rights were violated.”

Equally important, Pope Francis has helped internationalize and humanize the issue. The Abe administration has framed the Comfort Women issue entirely as a history problem with South Korea. The truth is that women throughout the Indo-Pacific region were the victims of the Imperial Army and Navy. The stories the women tell from the Andaman Islands to New Guinea, by Dutch gentry to Taiwanese aboriginals are shockingly similar.

As contemporary research has shown, sexual violence in conflict affects whole communities and generations. Recently, a Dutch woman came forward describing how as a four-year-old she waited daily on the steps of St. Xavier Church in the concentration camp at Moentilan, Java for her mother. Only as an adult did she learn that her mother’s lifetime nightmares were from being repeatedly raped by Japanese officers who had made the Church their headquarters. The mother was one of many “uncounted” Comfort Women.

Francis tacitly confirmed that the issue is not one of politics or diplomacy, as Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga repeats. But it is also not one of history as Suga and Abe want us to believe. Instead, it is a timeless humanitarian concern that can only be resolved through humanitarian action. The Pope returned the Comfort Women discussion to where it belongs—which is to comfort the victims.

But the Abe government has politicized the Comfort Women issue. The most unsettling omission in the Abe administration’s discourse on the Comfort Women is the failure to acknowledge the Batavia War Crimes trials. A 1947 Tribunal found a number of Japanese officers guilty of entering a civilian internment camp to forcibly select thirty-five girls and bring them in military vehicles to a military brothel in Semarang (Indonesia). The Batavia trial thus recognized the "forced prostitution" (to use the Dutch government's terminology) of women as a war crime.

Oddly, in 2013, there was a Cabinet Decision admitting that the trial documents were part of the official Japanese government records supporting the Kono Statement. These did not seem to have been considered in the recent government “review” of how the Statement was drafted. Instead, the Abe Government continues to parse the traumatic memories of Korean former Comfort Women and Japanese soldiers looking for discrepancies to question this sordid history.

The omission can lead to the disturbing conclusion that discrediting the Comfort Women, no matter the evidence, has a greater goal. This is to set aside any legal record or proceeding prosecuting Japan’s war criminals. The ease at which the Batavia trial verdict has been disregarded has implications for the verdicts of all the hundreds of war crimes trials throughout the Pacific after the war, especially the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

Undoing the postwar regime and its “masochistic” history is a stated objective of the Abe administration. The path to regaining Japanese pride and independence, according to Mr. Abe and many in his administration, means not accepting the results of the Tokyo Tribunal and not being a victim to its “victor’s justice.” By ignoring the Batavia verdicts, the Abe government takes the first step to challenge the decisions of The Tribunal.

Paying homage at Yasukuni, the spiritual symbol of Imperial Japan is a ritualistic swipe at the Tokyo Tribunal. Yasukuni, where hundreds of war criminals are deified, which hosts a museum that celebrates Japan’s “liberation” of Asia and small shrines to the likes of the Kempeitai, does not accept Japan’s defeat or the condemnation of its war criminals. Thus, a visit or an offering sent is less about mourning than about a gesture as powerful as the Pope’s in affirming a certain point of view as fact.

"The Pope returned the Comfort Women discussion to where it belongs—which is to comfort the victims."

Mindy Kotler

August 31, 2014

inShare

In the end, it is not about the dead. As the Pope showed, it is the living that need peace. Maybe Abe should spend less time with the dead. At every international visit, the prime minister has made a point of visiting war memorials. On his recent trip to Papua New Guinea, Abe visited two memorials to Japan’s fallen at Wewak. He made no mention of how this horrific final campaign descended into barbarism and cannibalism. Nor was there mention of the thousands of POWs, mainly Indian and Australian, killed through starvation, overwork, disease or target-practice on the island.

At this year’s August 15th anniversary for Japan’s war dead, Abe, unlike past prime ministers, made no mention of apology for Japan’s aggression. Again, this is viewed as a rejection of the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal’s judgments.

Central to Japan’s peace treaty with the Allied governments in 1951, was acceptance of the verdicts of the Tokyo Tribunal. Abe’s rallying the dead to abandon the Tribunal’s verdicts does not engender trust among Japan’s allies or foes. Thus, it is time for Prime Minister Abe to make an important gesture to reassure his critics. He can affirm that he has no plans to ignore or repudiate the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal. Saying that he, for now, inherits the Murayama apology—he walked out of a parliamentary vote on this apology in 1995—is not enough. He needs to embrace these ideas.

Pope Francis’ quiet inclusion of the Comfort Women in his mass was a humanitarian gesture. It was an acceptance that no woman at any place or time should be subjected to the mercy of her captors. The political debate over Comfort Women to exonerate Imperial Japan’s war conduct has been damaging to modern Japan’s international image. Prime Minister Abe is best advised to affirm the verdicts of history and offer an unequivocal humanitarian response to the surviving Comfort Women in Korea and in other places.

Mindy Kotler is the director of Asia Policy Point.

Image: Flickr/Official Republic of Korea/CC by-sa 2.0

The Pope's Verdict on Japan's Comfort Women

"The Pope returned the Comfort Women discussion to where it belongs—which is to comfort the victims."

Mindy Kotler

August 31, 2014

Before his final mass in South Korea on August 18, Pope Francis met with seven elderly ladies who had been Comfort Women. As teenagers during World War II they were trafficked by Imperial Japan to be sex slaves. Military records on the operation of a comfort station show that the girls had to service not only soldiers and sailors, but also Japanese government and corporate officials.

The Pope bent down and clasped the frail hands of each woman. One offered him a butterfly pin, a symbol of their lost innocence, which the Pontiff immediately fastened to his vestments and wore throughout the service. Prior to the mass, he was handed a letter from the Dutch former Comfort Woman, Jan Ruff O’Herne, who at 92 could not travel from her home in Australia to meet him. She wanted him to know that before she was chosen by Japanese Army officers in her concentration camp on Java and raped in a Semarang military brothel, her dream was to become a nun.

The women received more than the Pope’s blessing. They received affirmation that their history was believed and their suffering real. Francis has championed the elimination of human trafficking and preached on the evils of sexual slavery. By a simple gesture, he included their experience with all victims caught up in sexual violence. He understands that rape is a weapon of subjugation and humiliation. Unlike Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe, the Pontiff does not rationalize the Comfort Women experience with “the 20th century was a century where many human rights were violated.”

Equally important, Pope Francis has helped internationalize and humanize the issue. The Abe administration has framed the Comfort Women issue entirely as a history problem with South Korea. The truth is that women throughout the Indo-Pacific region were the victims of the Imperial Army and Navy. The stories the women tell from the Andaman Islands to New Guinea, by Dutch gentry to Taiwanese aboriginals are shockingly similar.